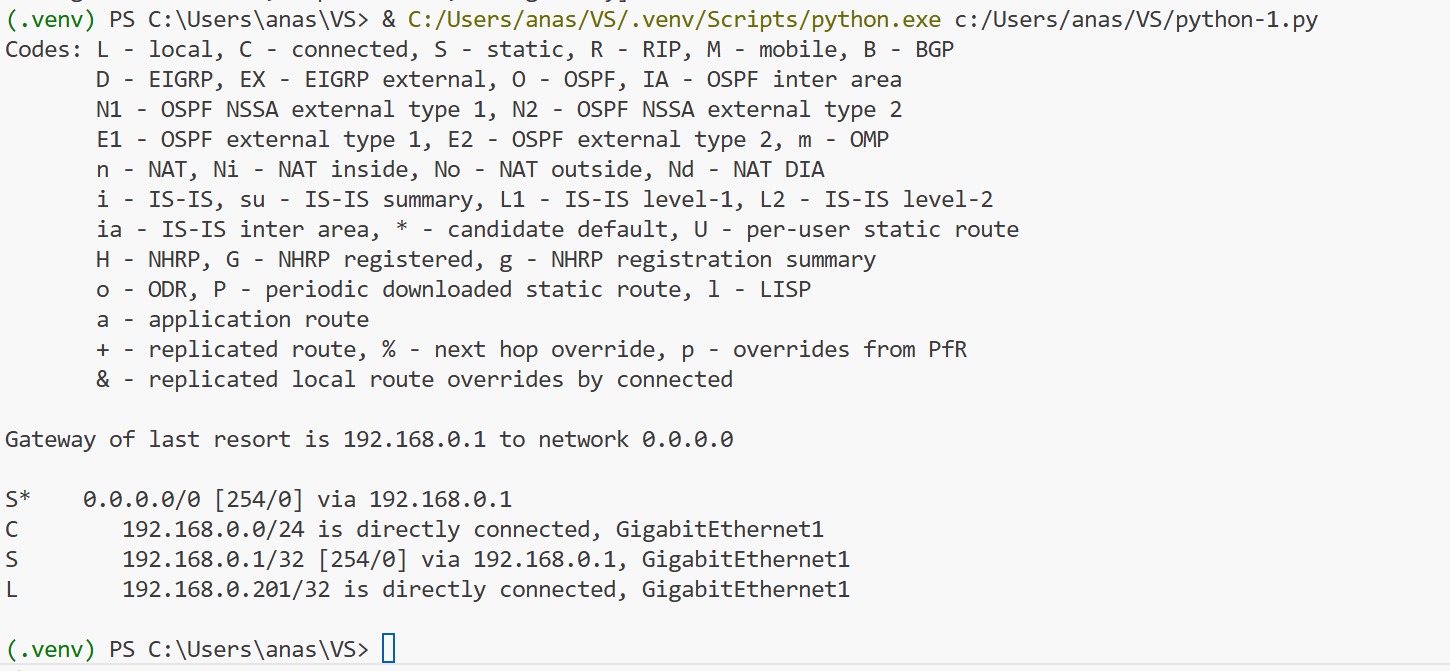

⊹ 94. CCIE Python ⊹

Python

Python Installation Guide

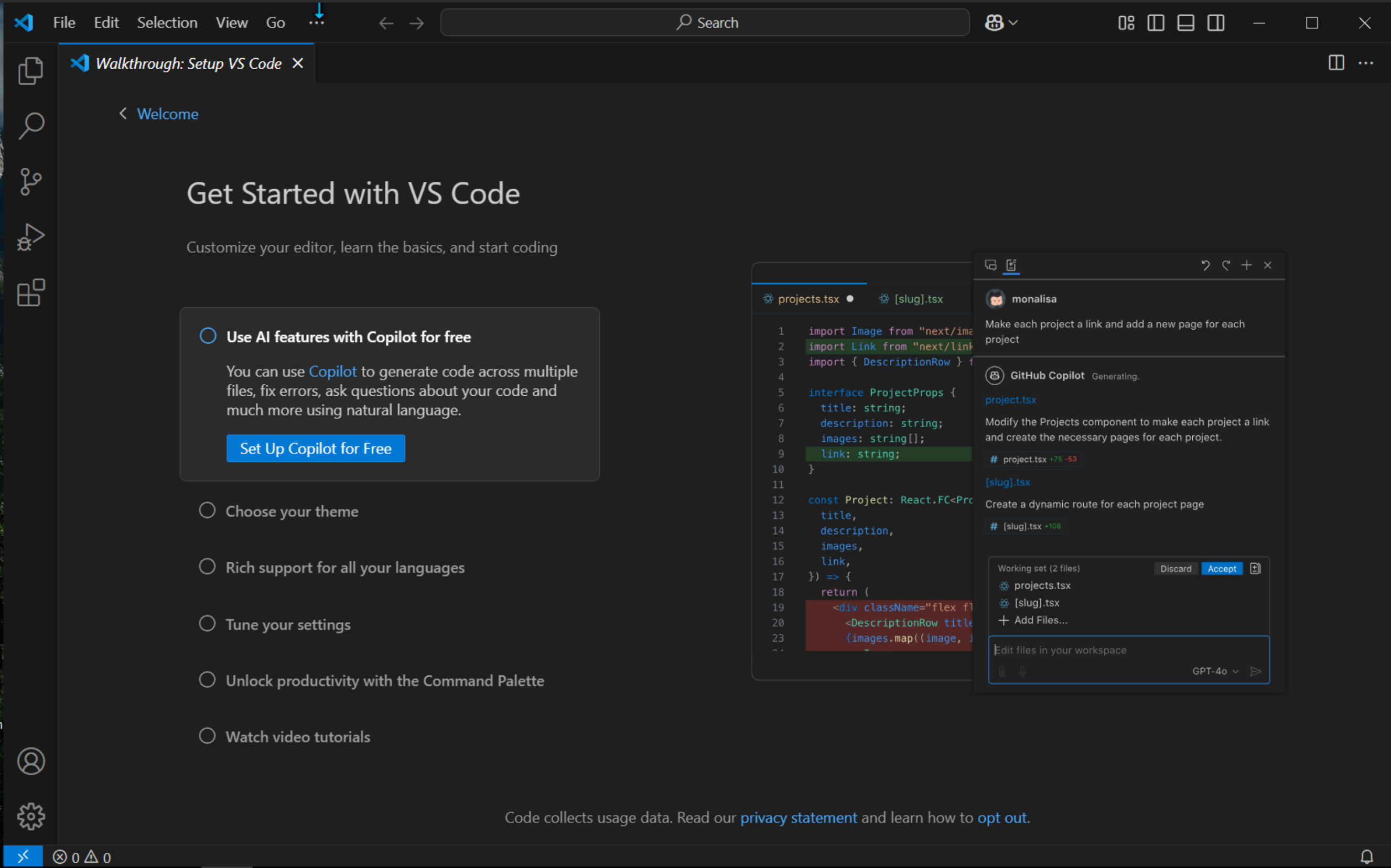

Download and Install Visual Studio Code from Microsoft

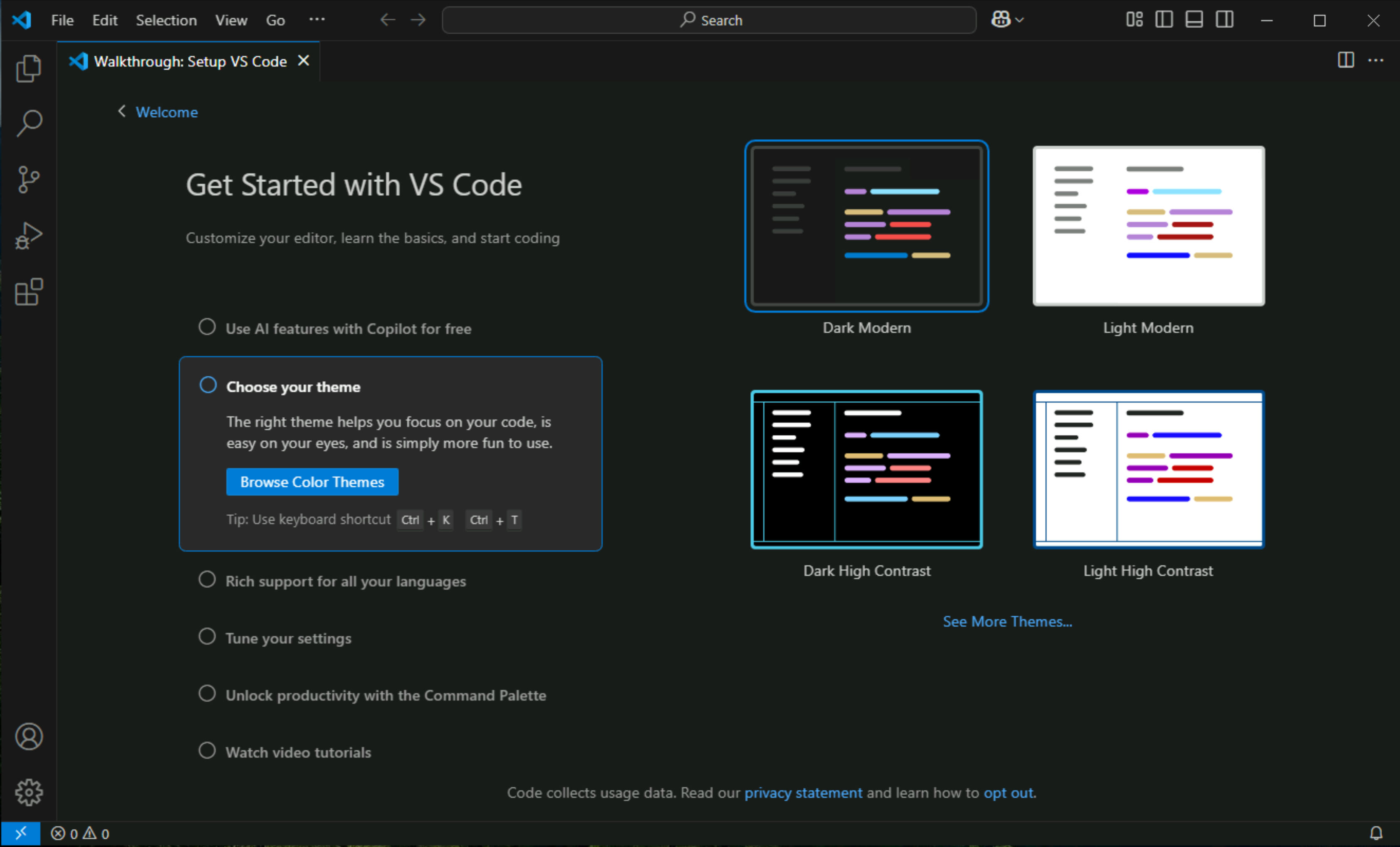

Choose dark theme because it is cool

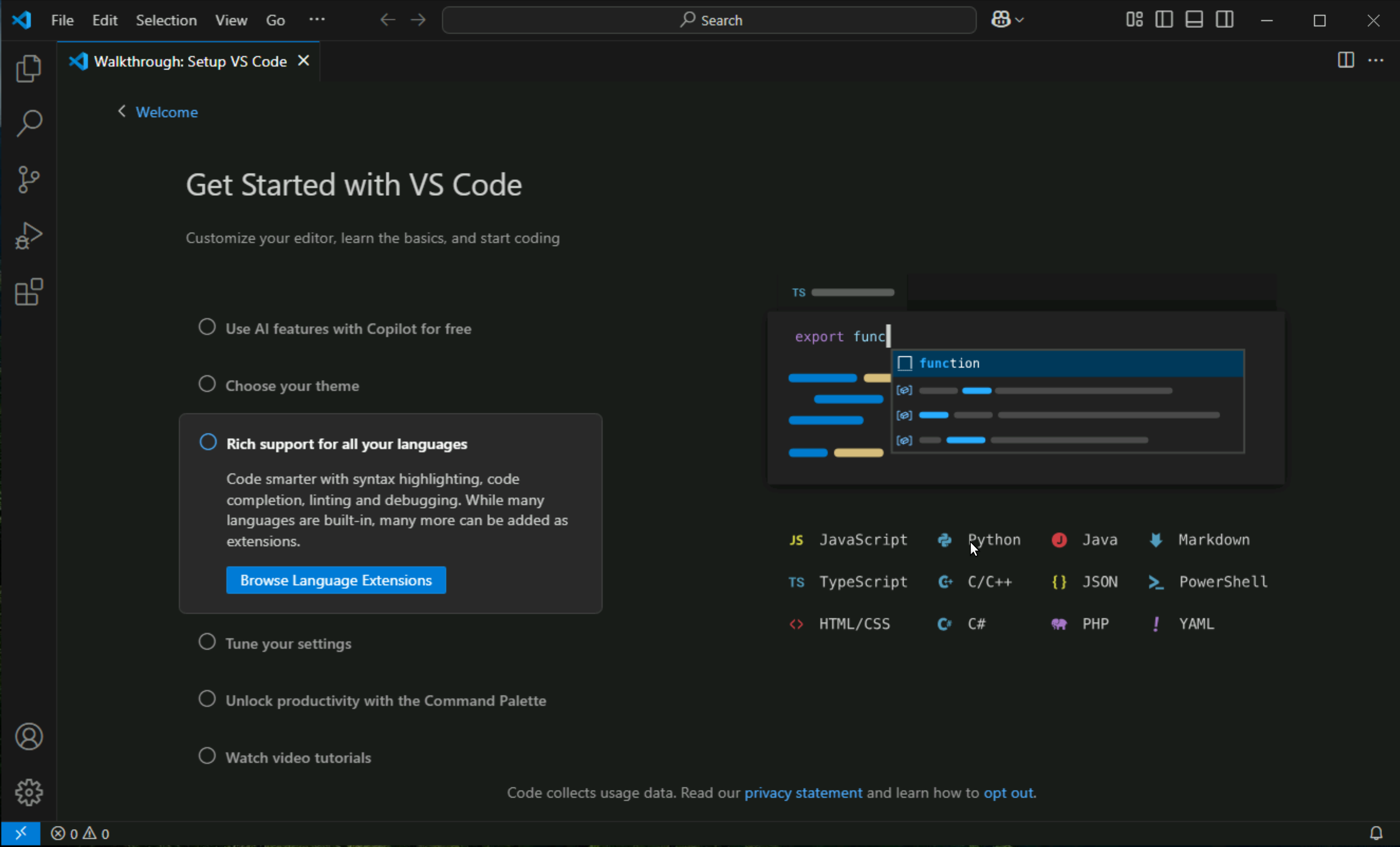

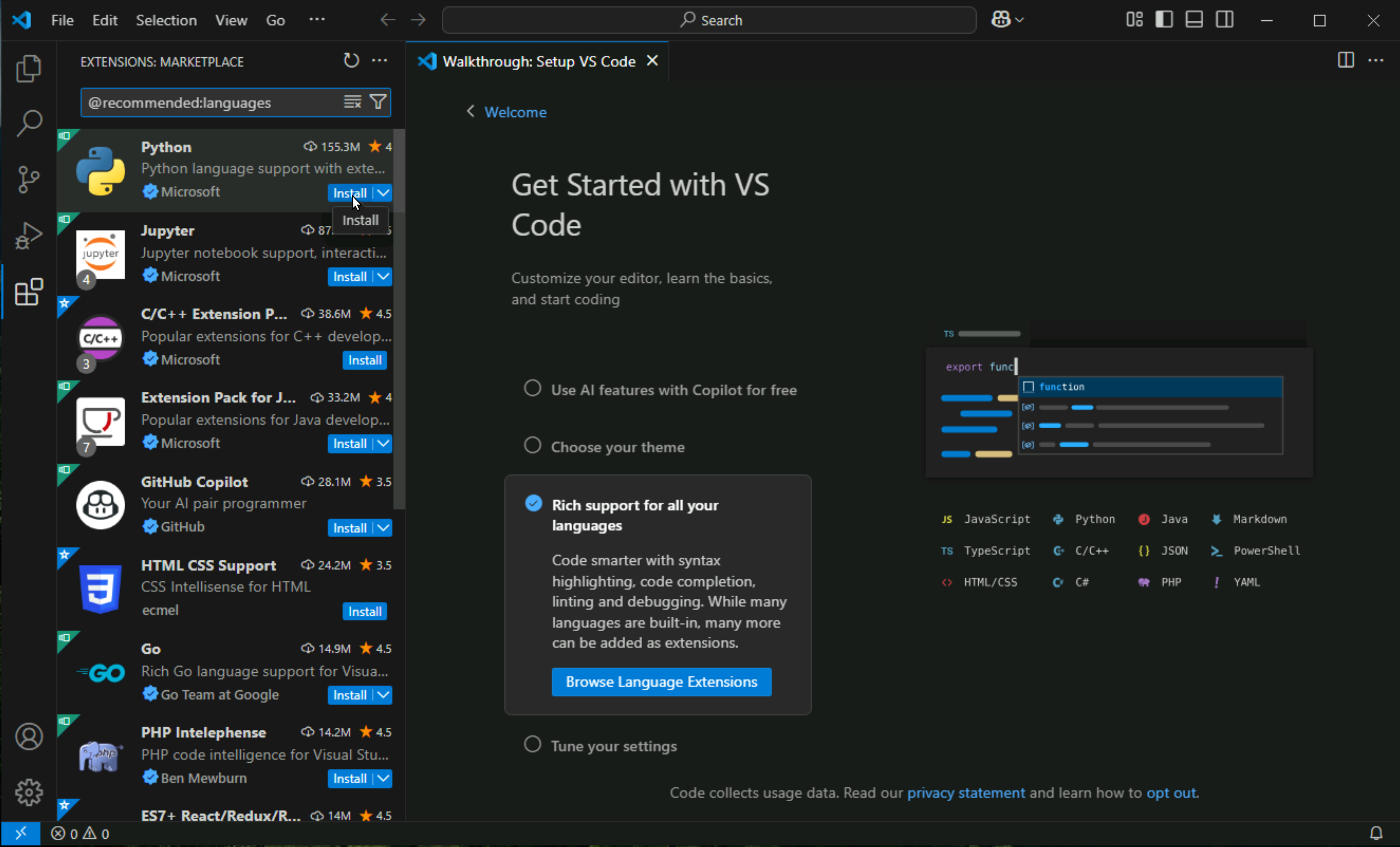

Click on python on the right side

Click on python > install

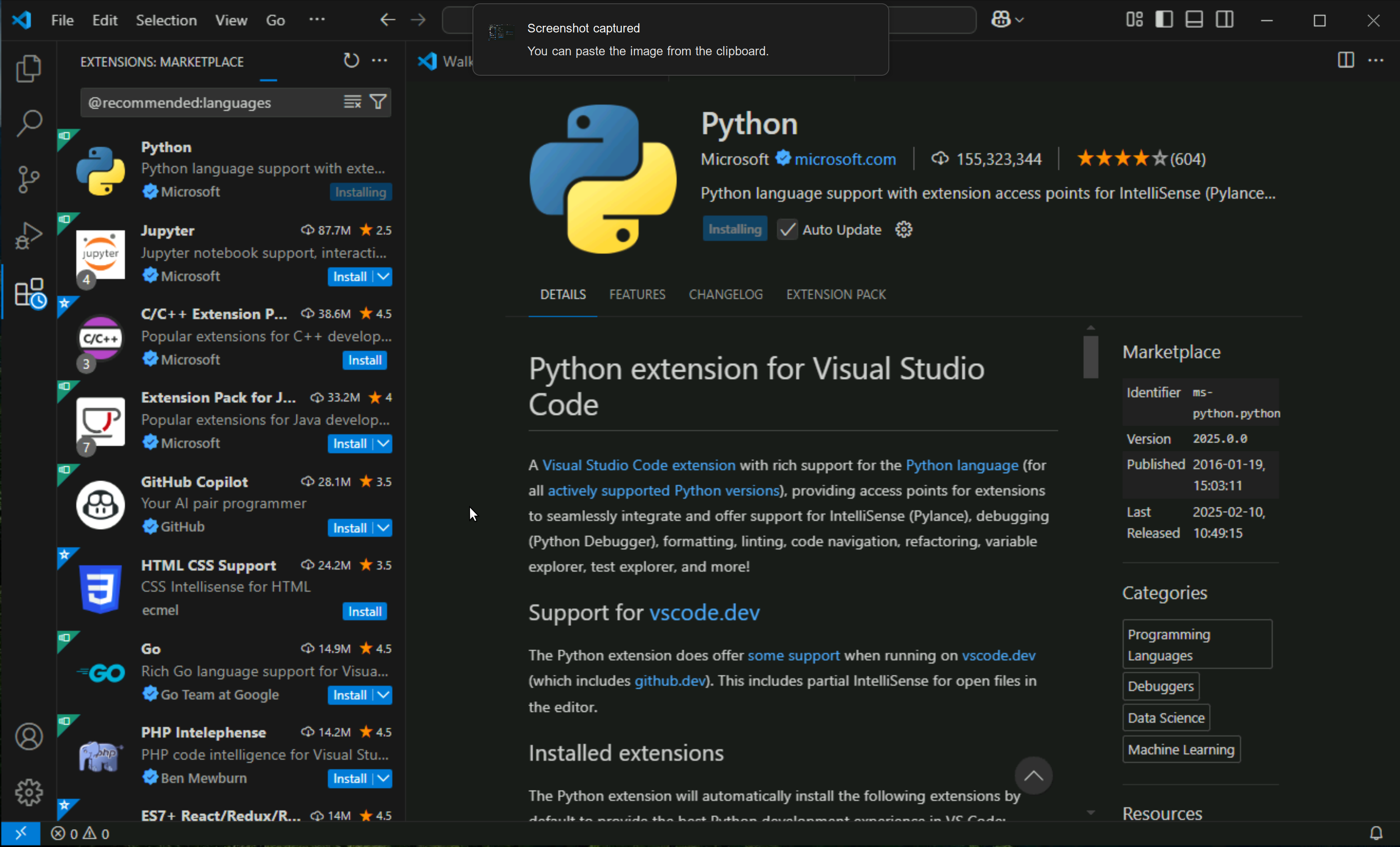

Wait for it to install, this is just the support for the language in VSCode but not the language or Python interpreter itself, we will download it from Microsoft’s store later

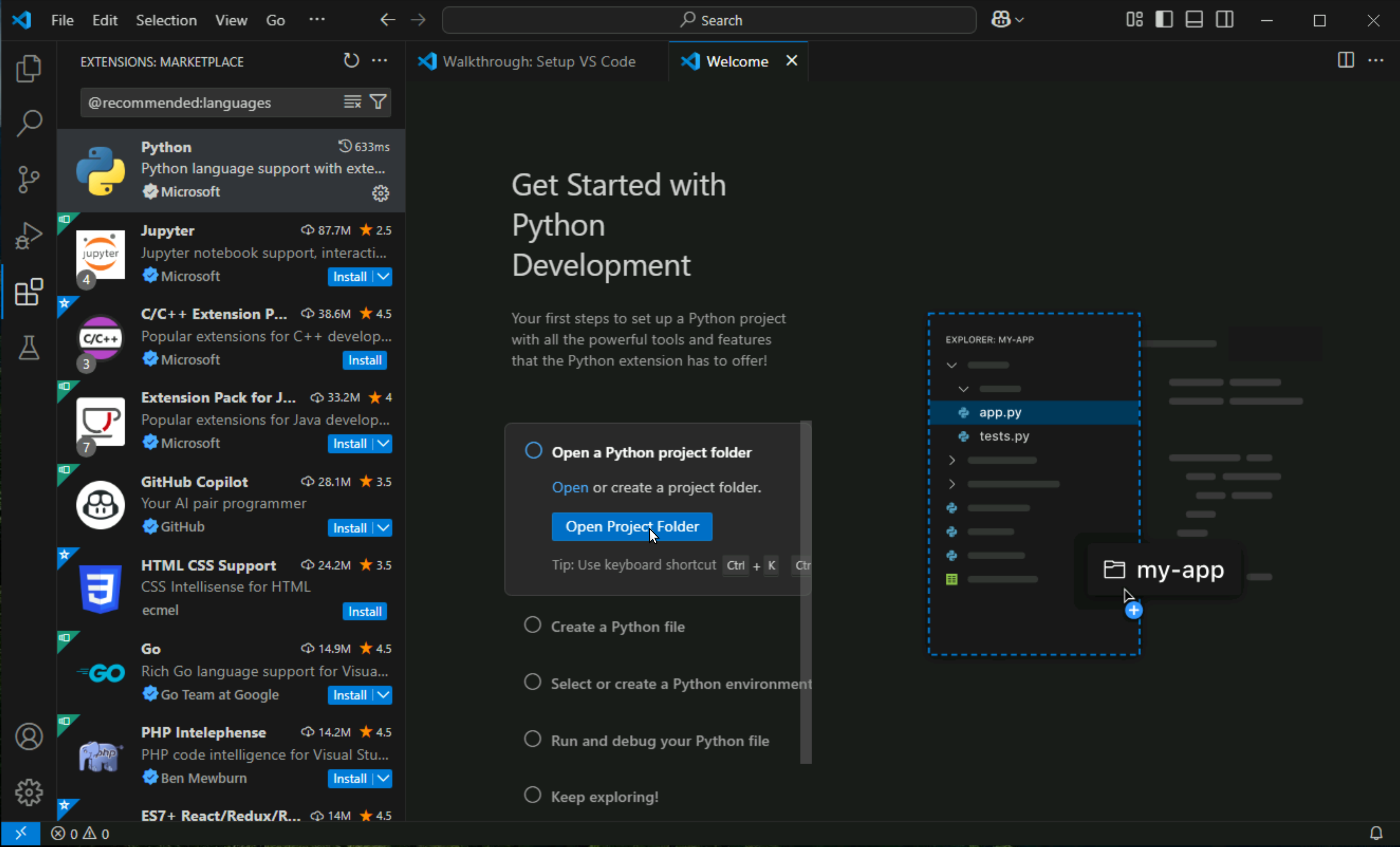

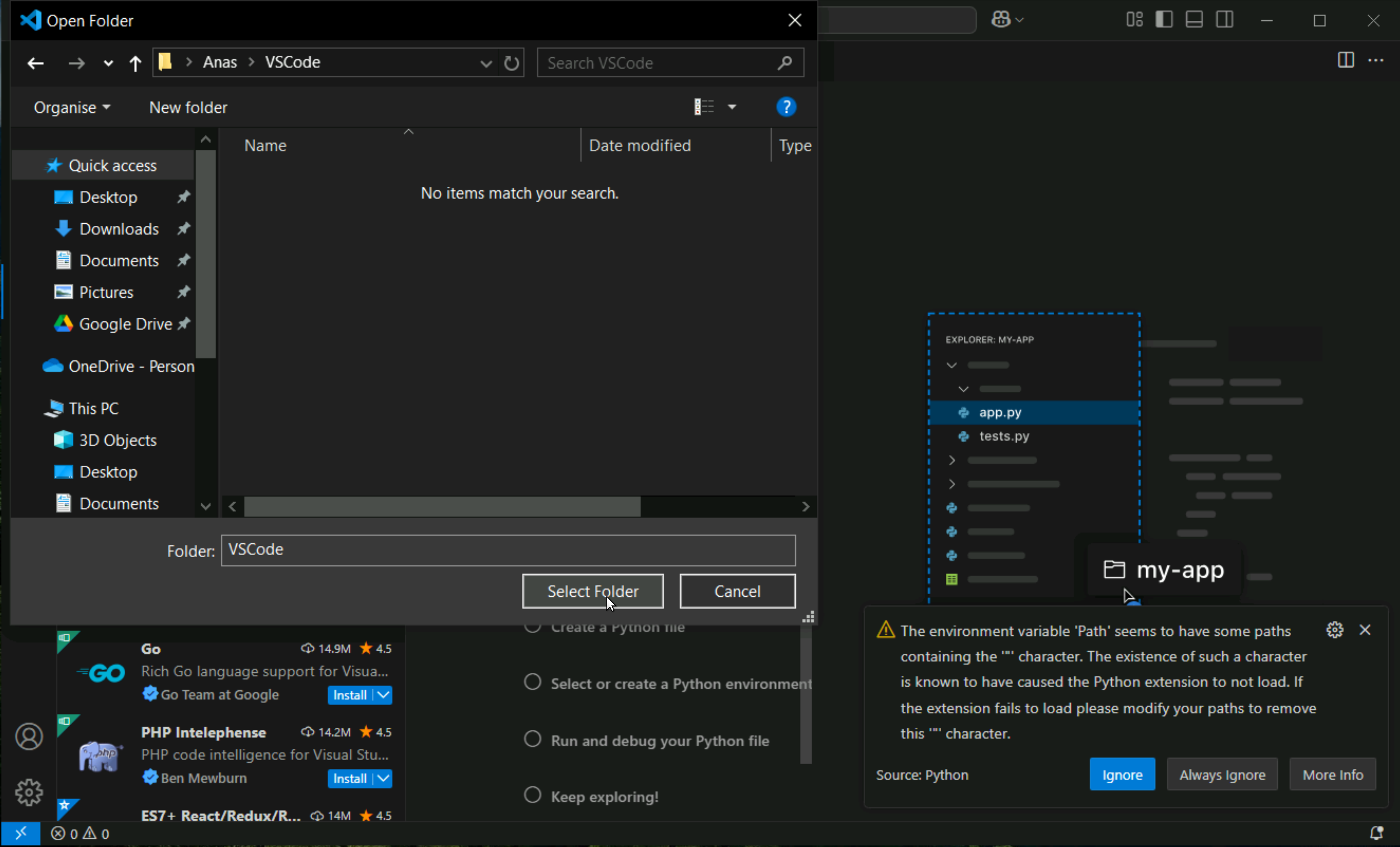

Click on Open Project folder

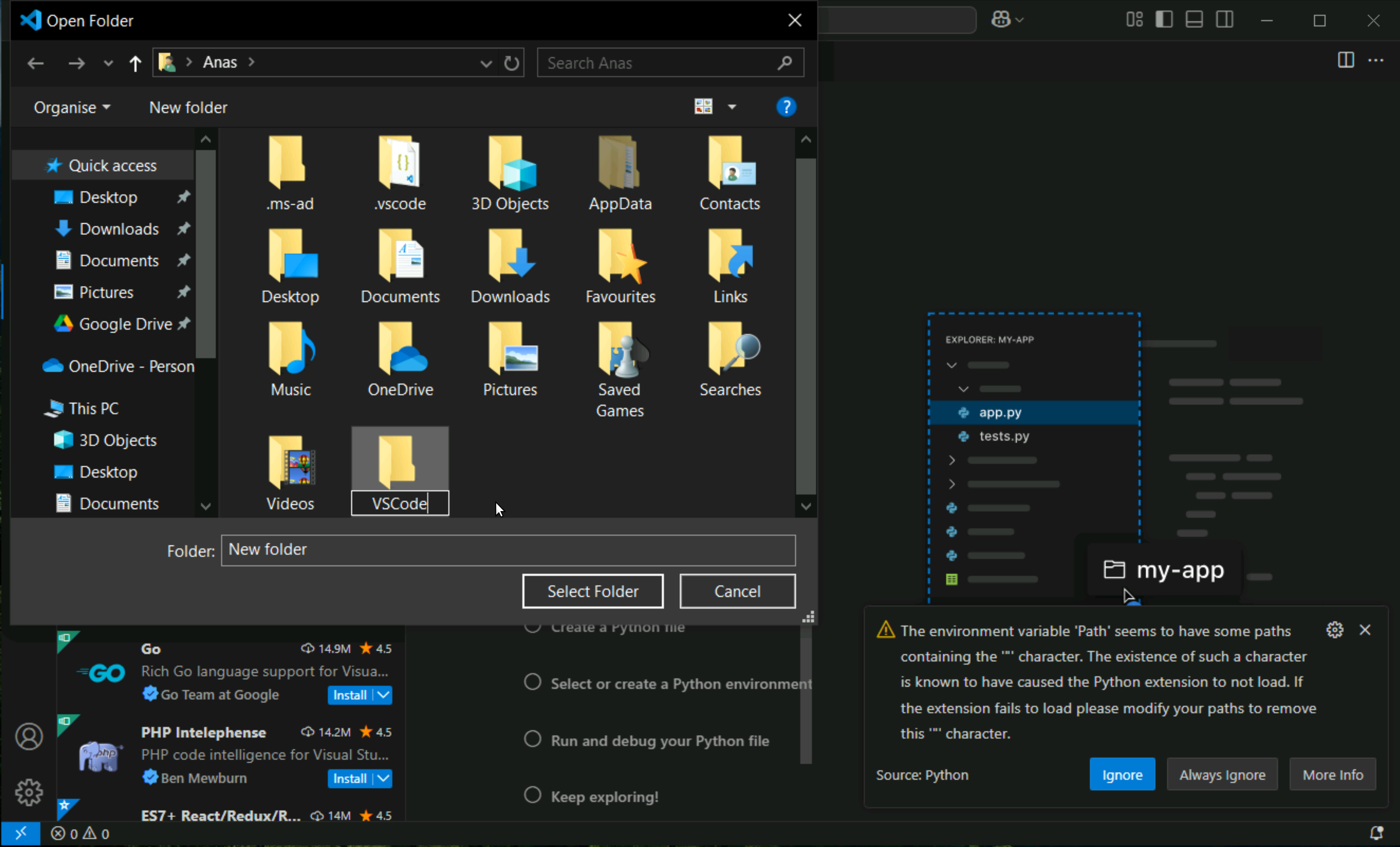

right click, create new folder and name it VSCode

Click “Select Folder”

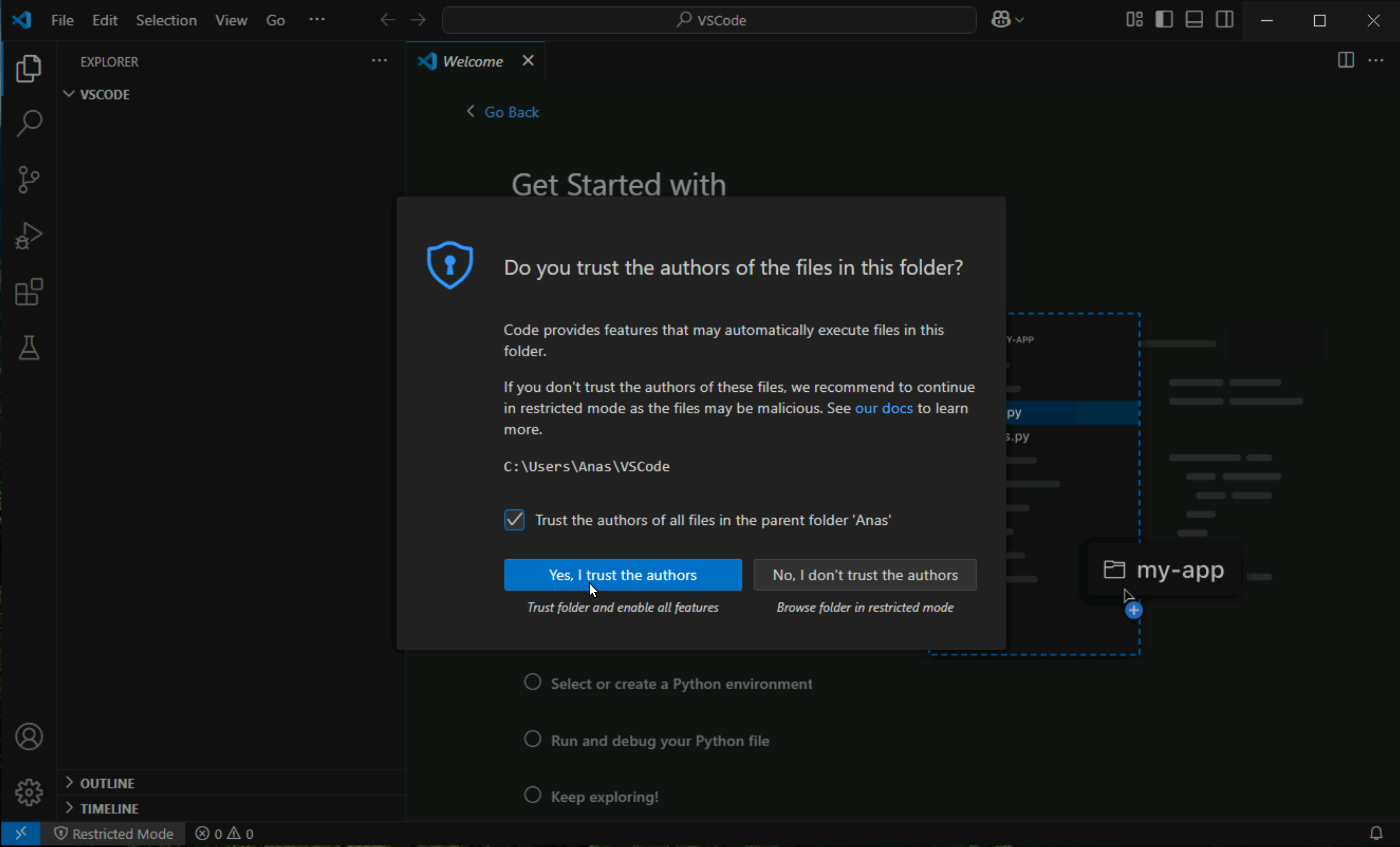

Tick that Trust option and Click on Trust button

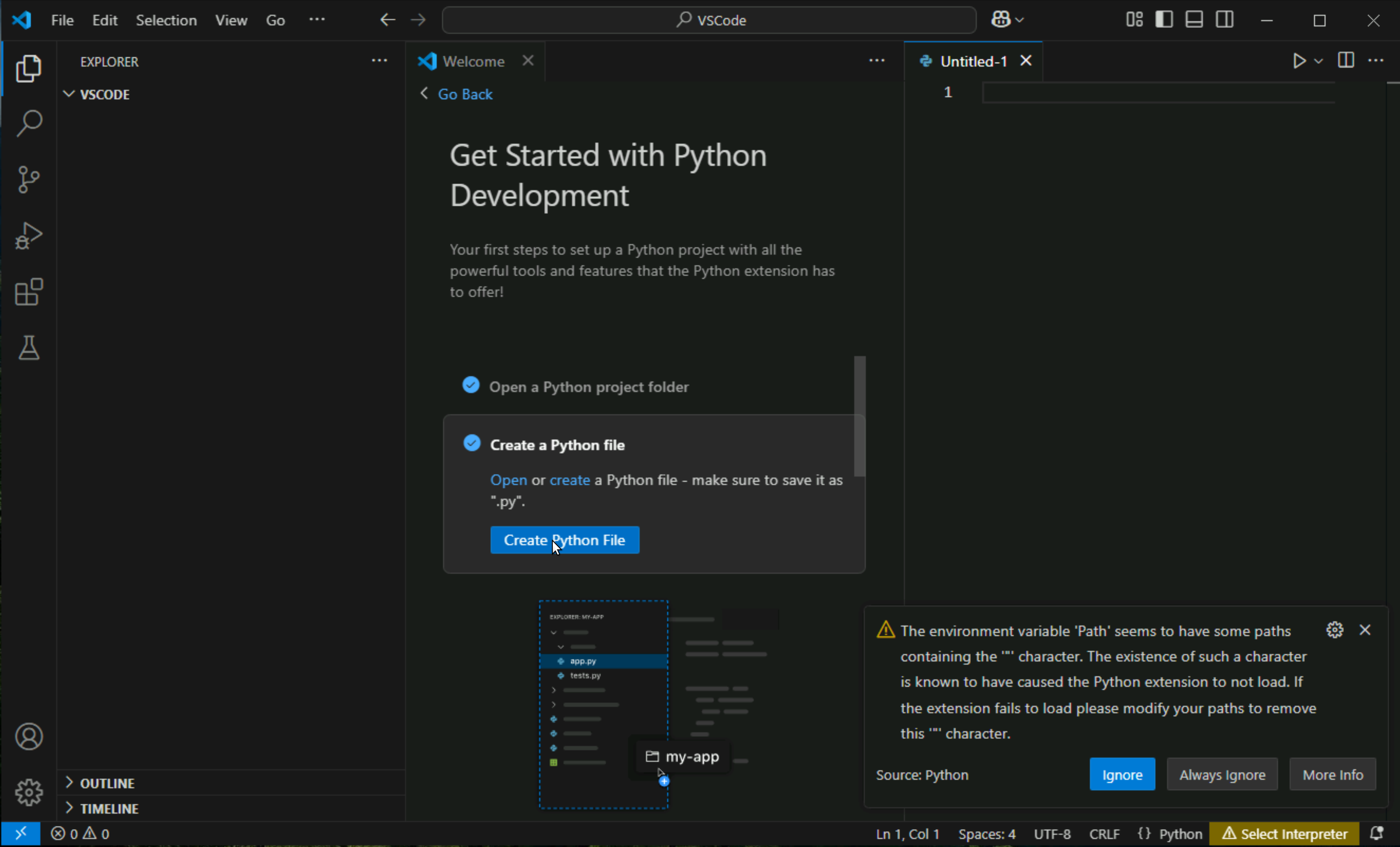

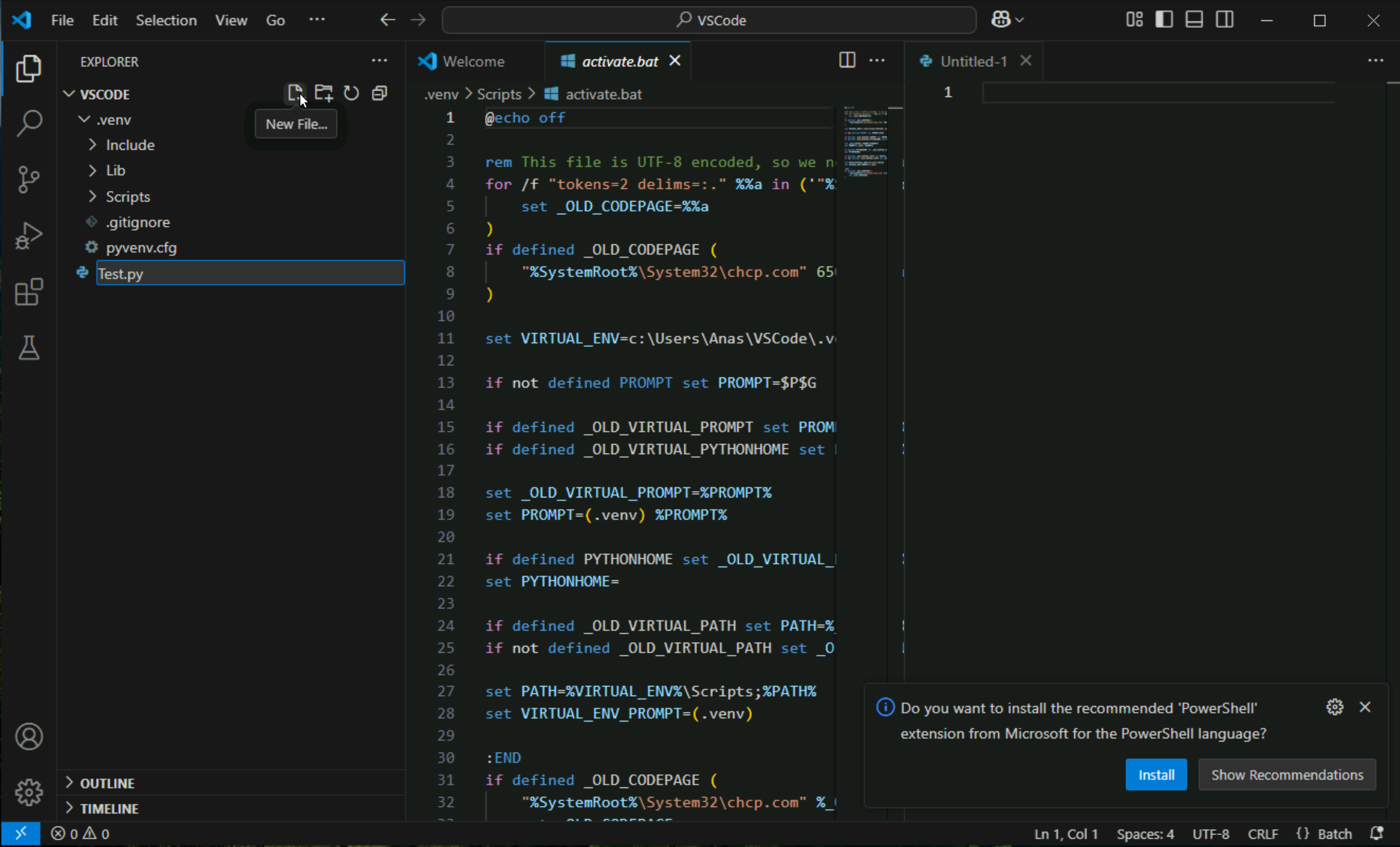

Click on Create a python file

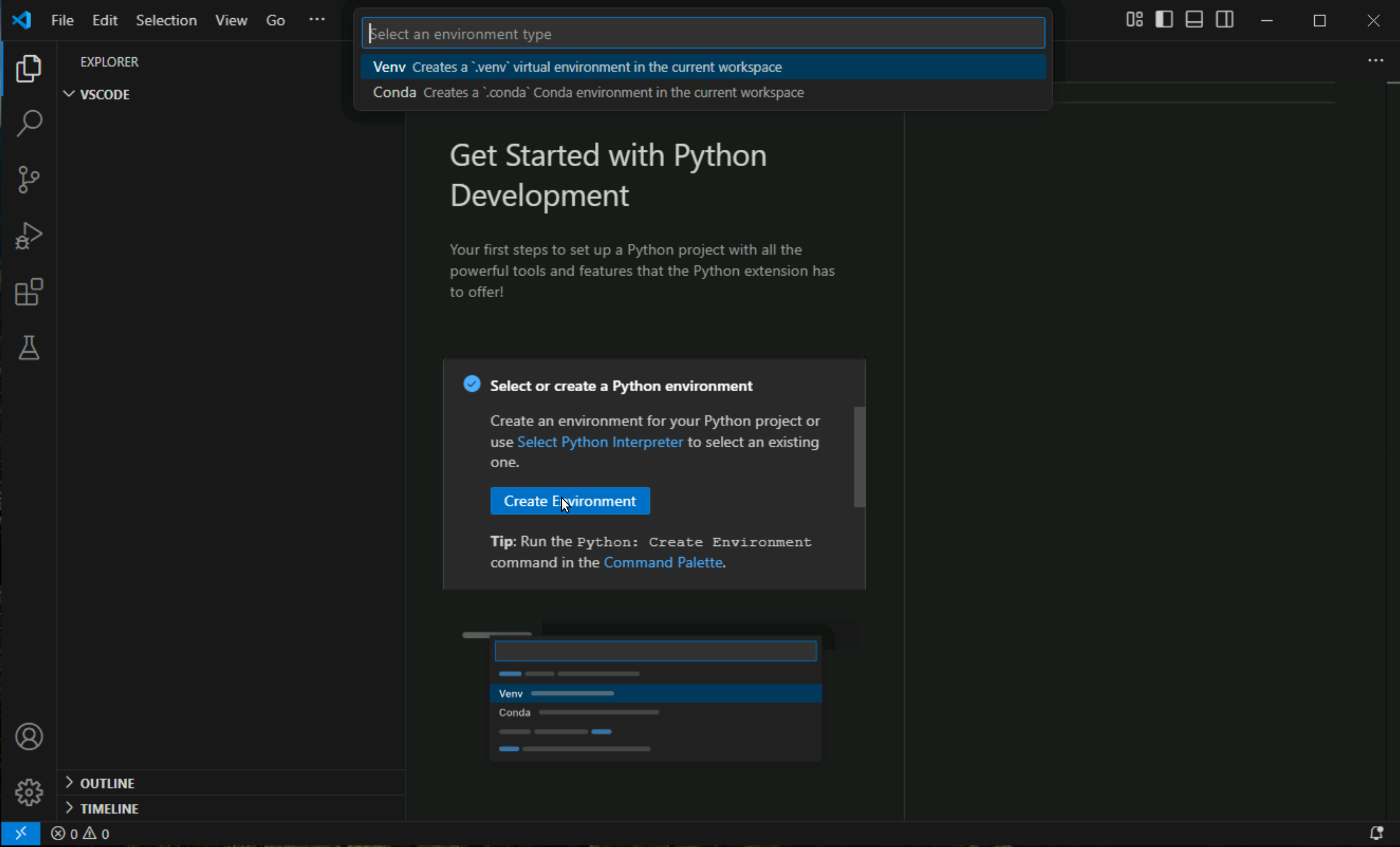

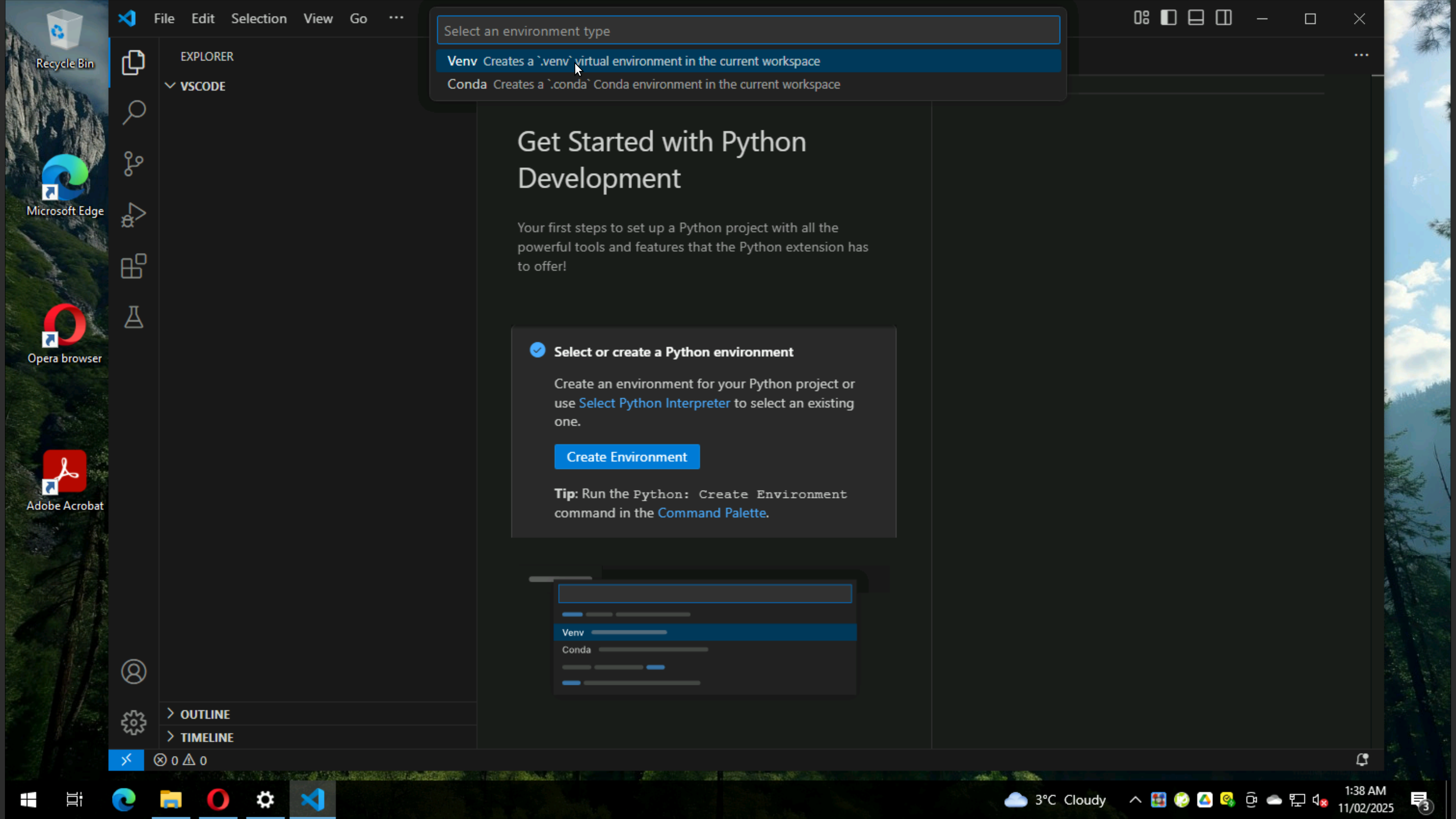

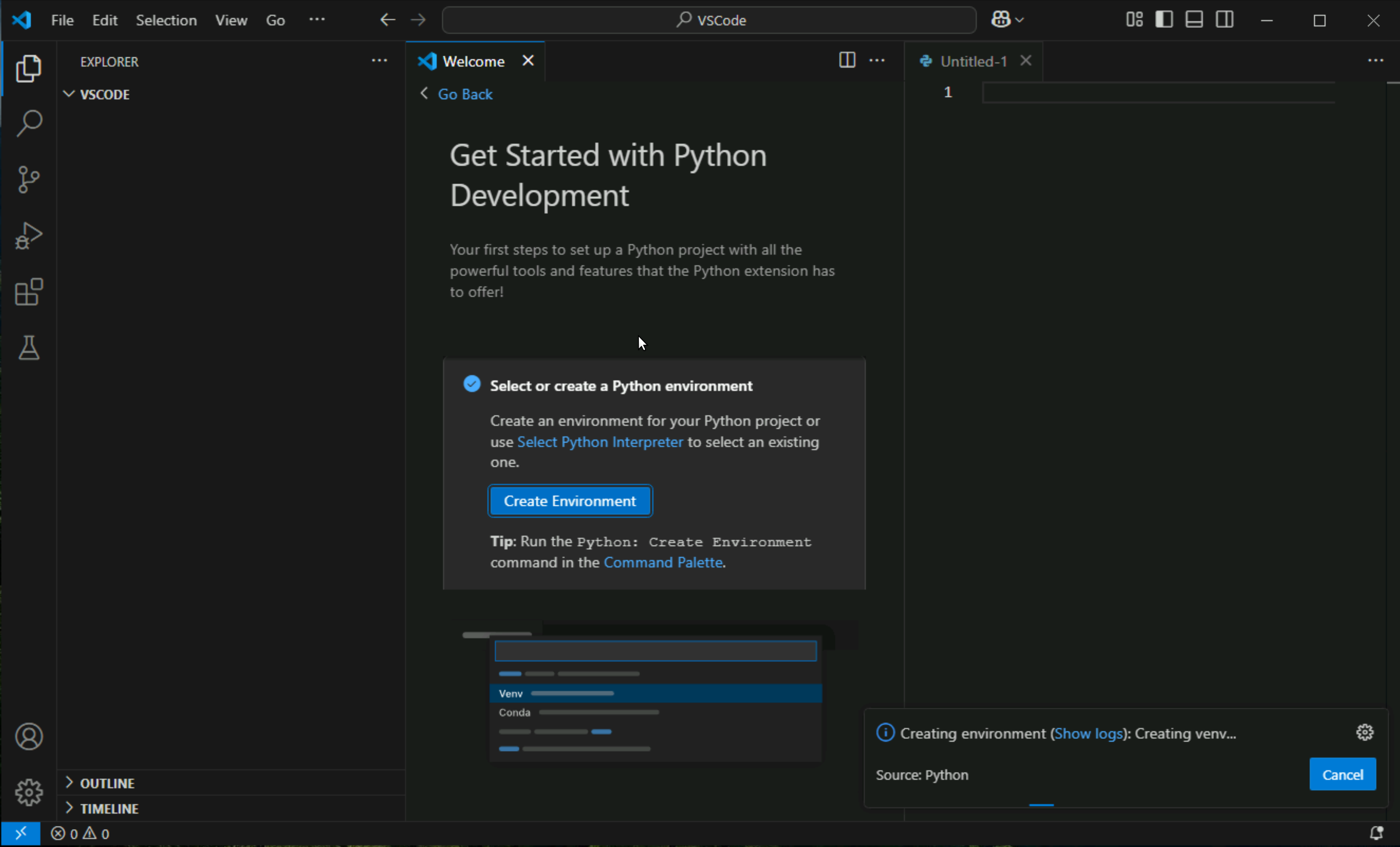

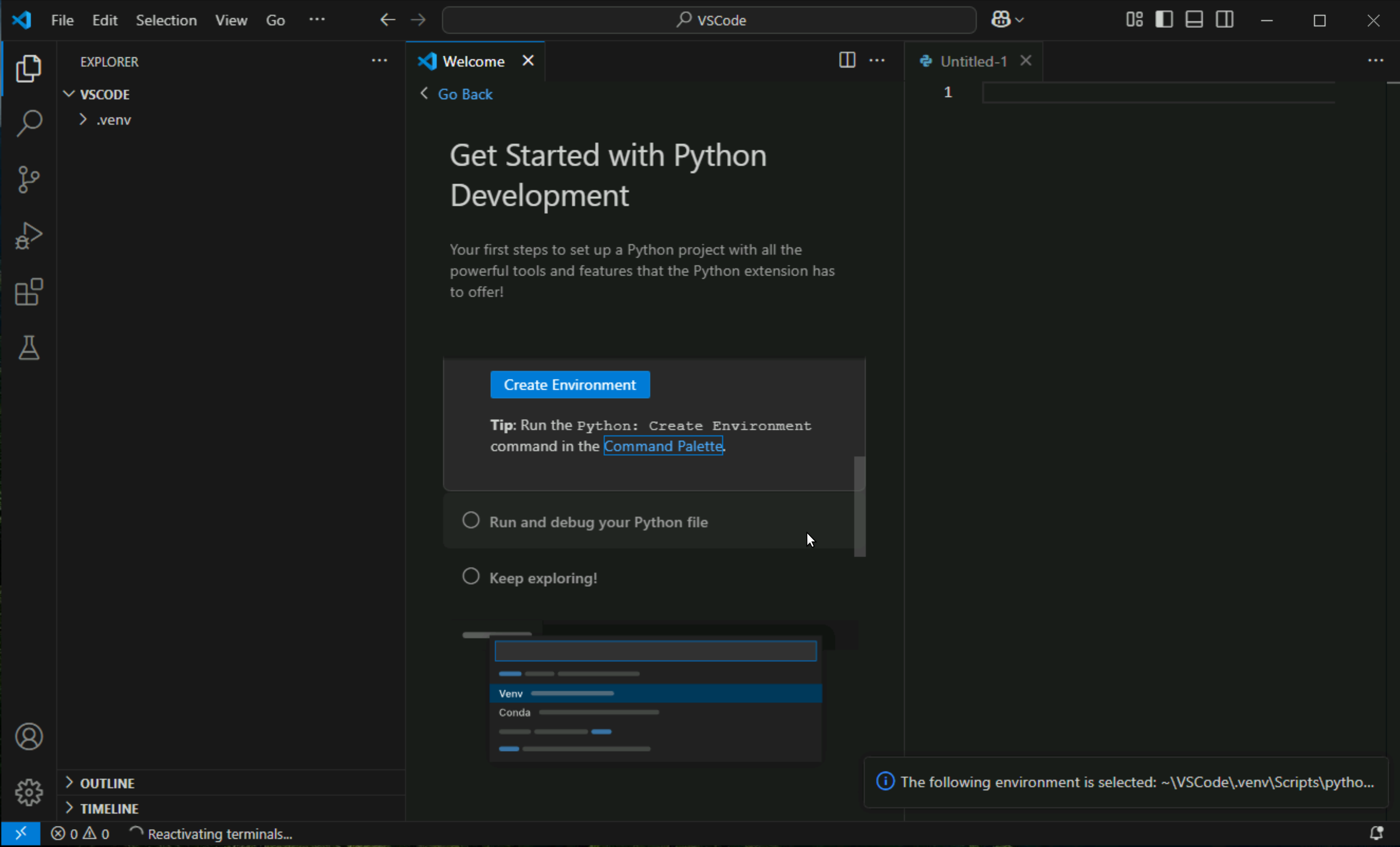

Click on create environment

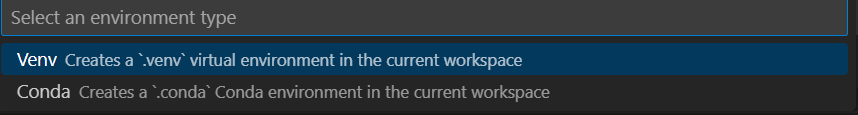

Click on Venv ( this will be explained later )

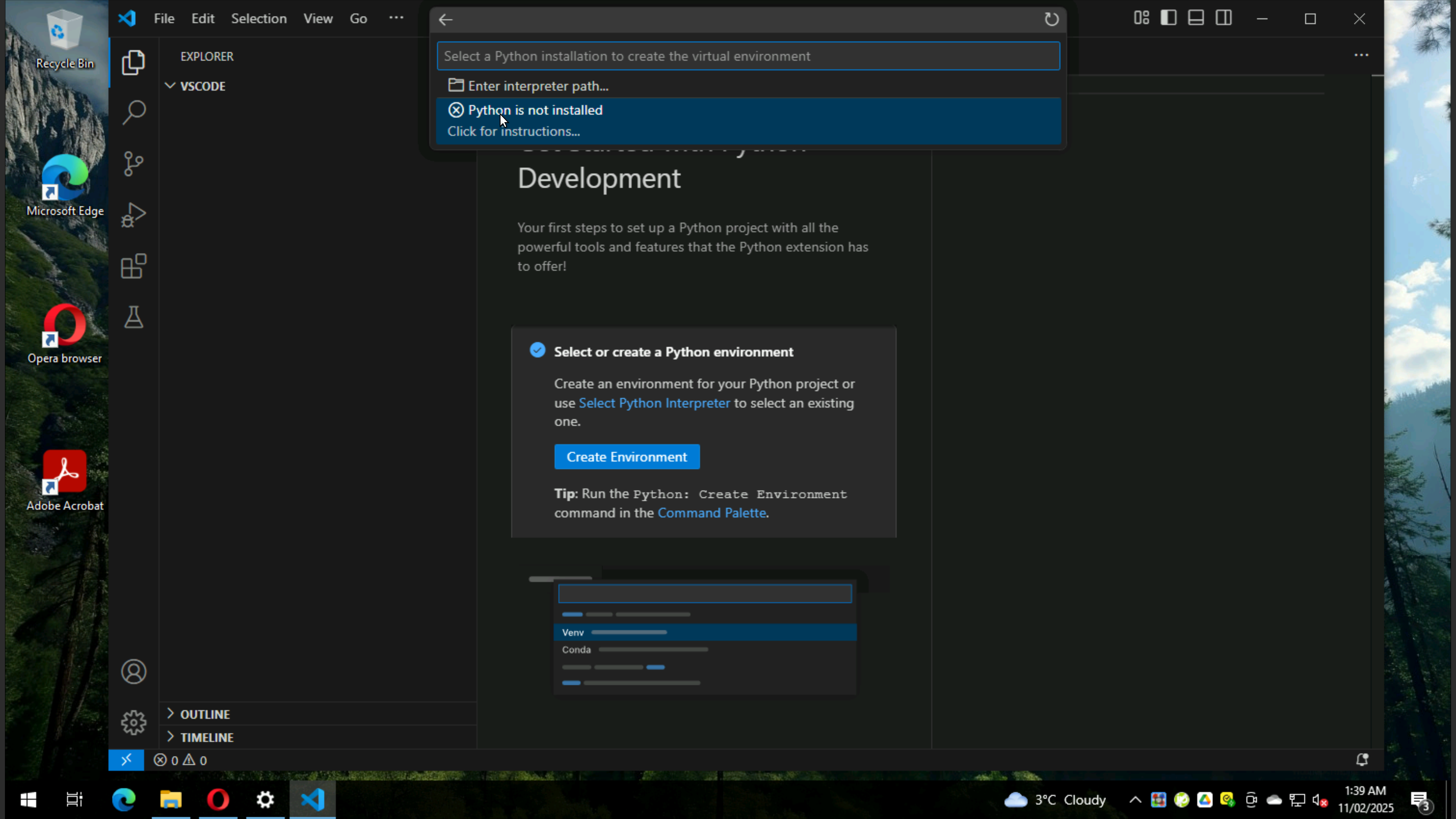

See message that Python is missing, but still click on it

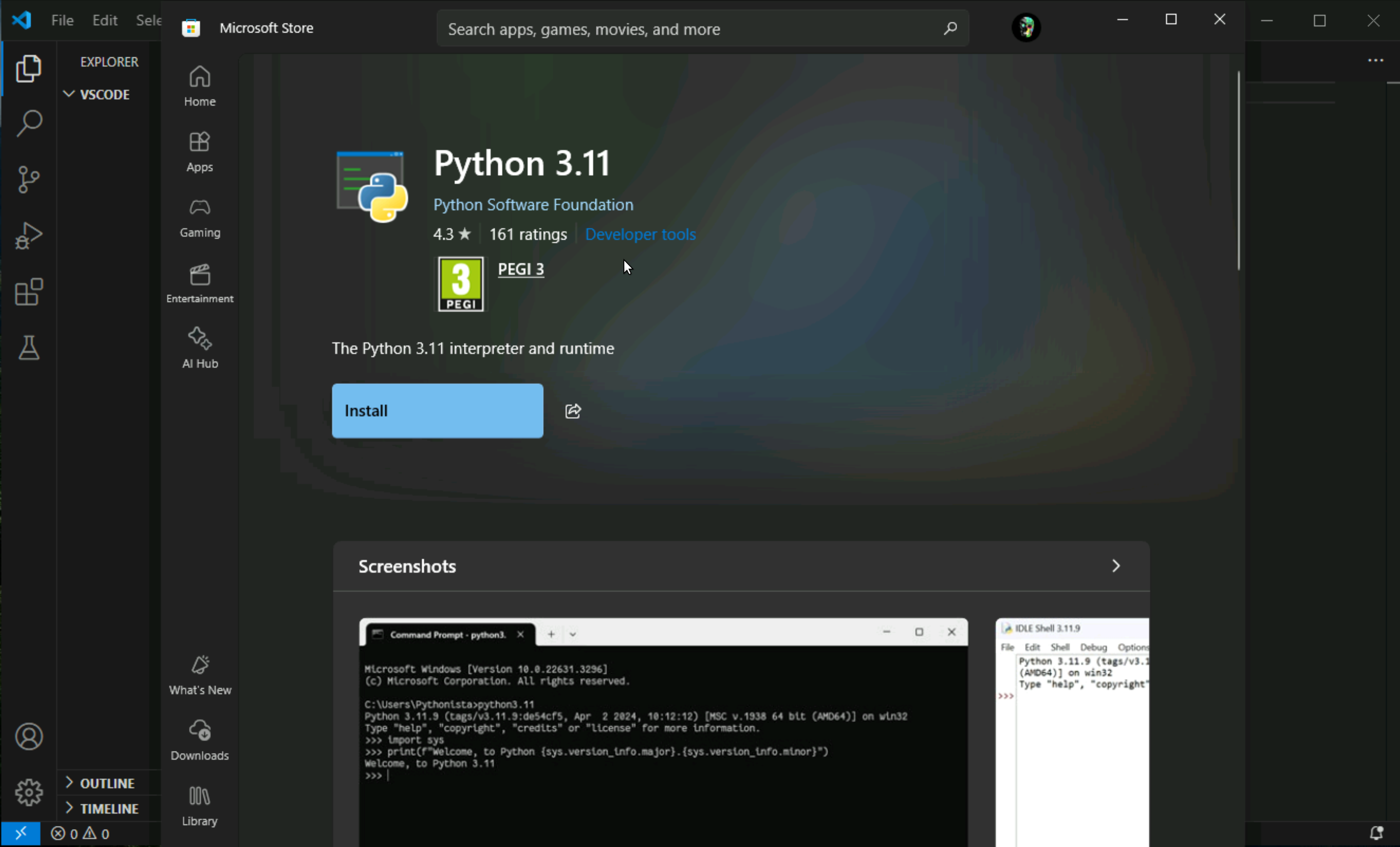

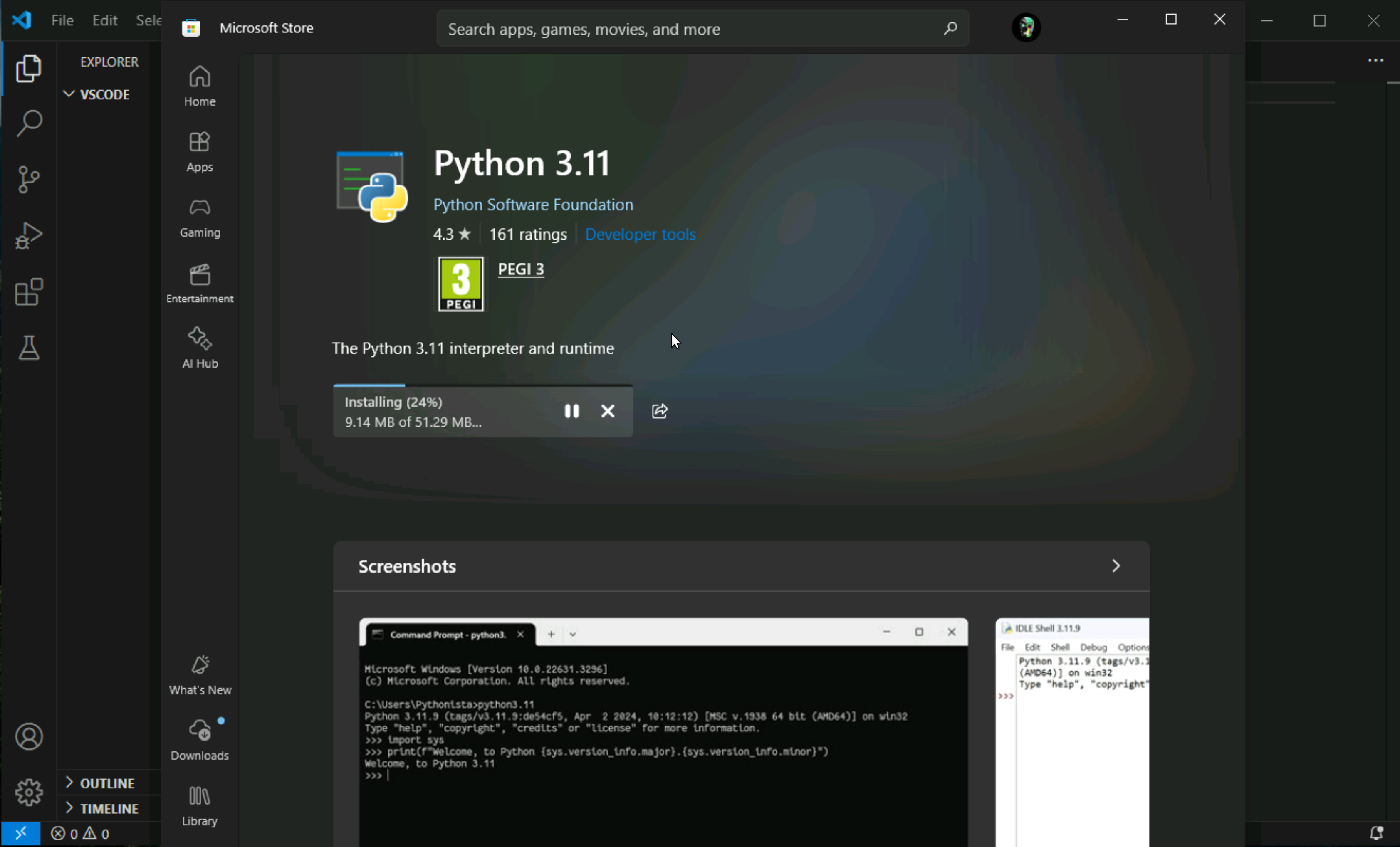

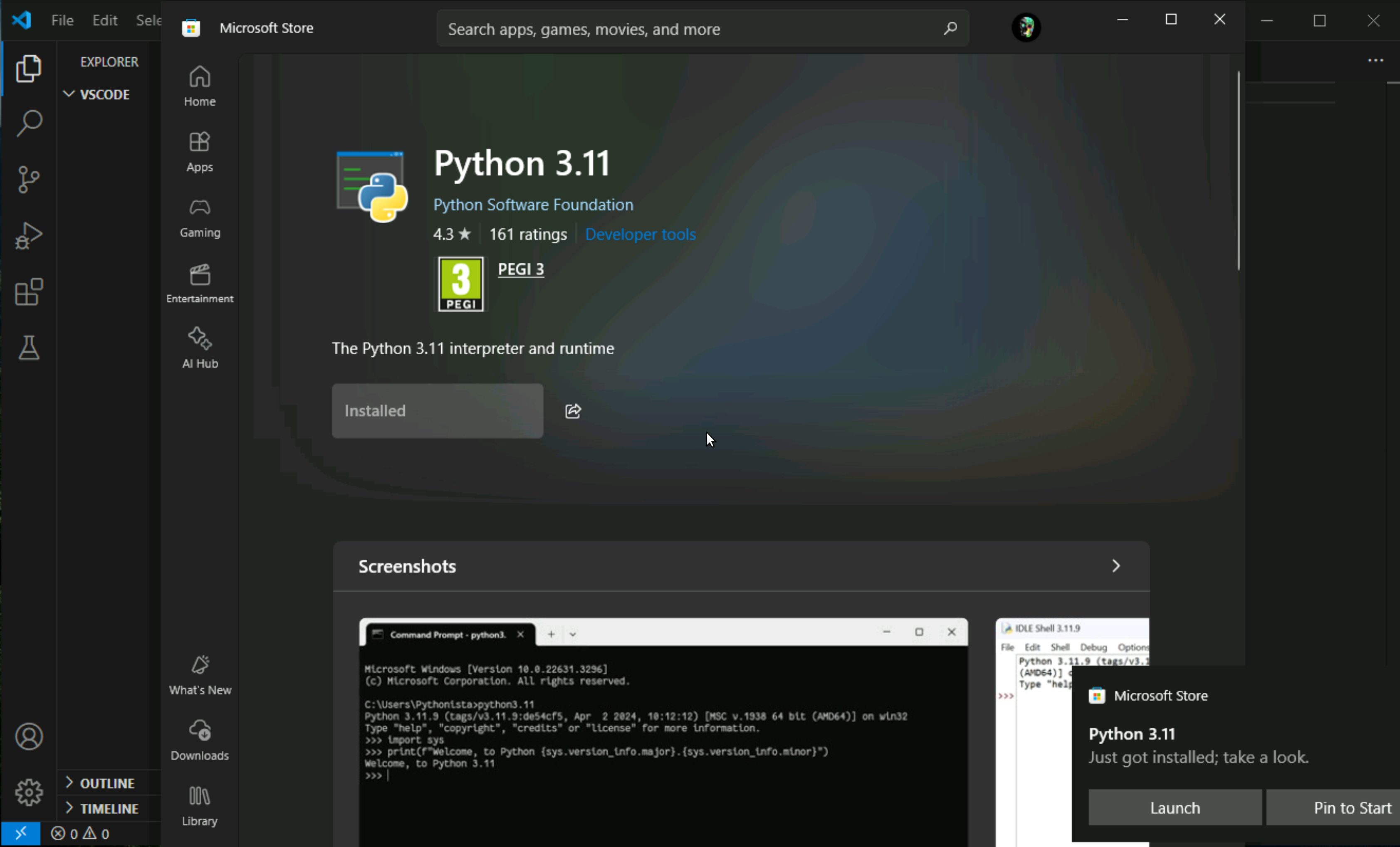

it will take us to Microsoft Store and click on install

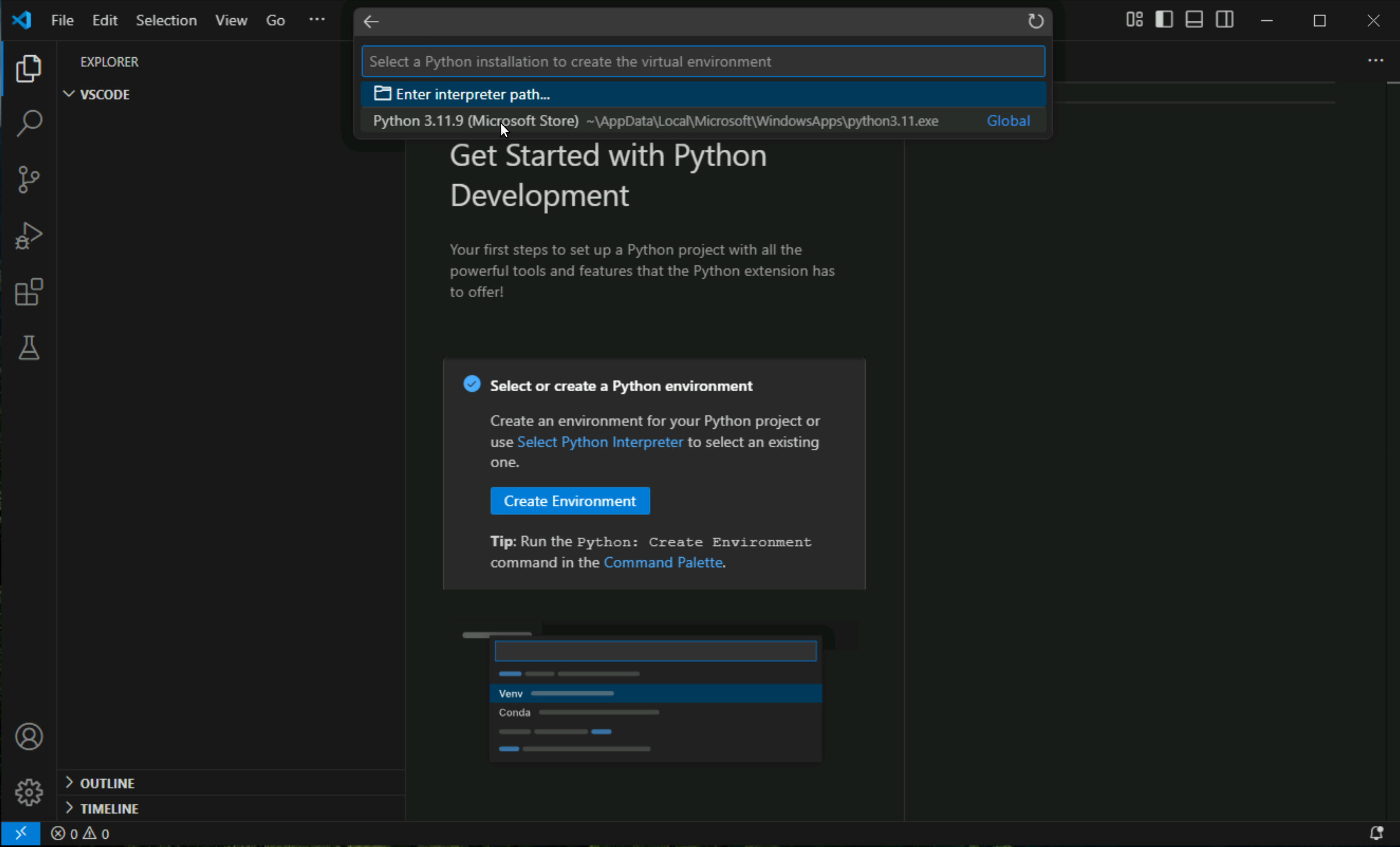

Once it is installed Python interpreter will show, click on it

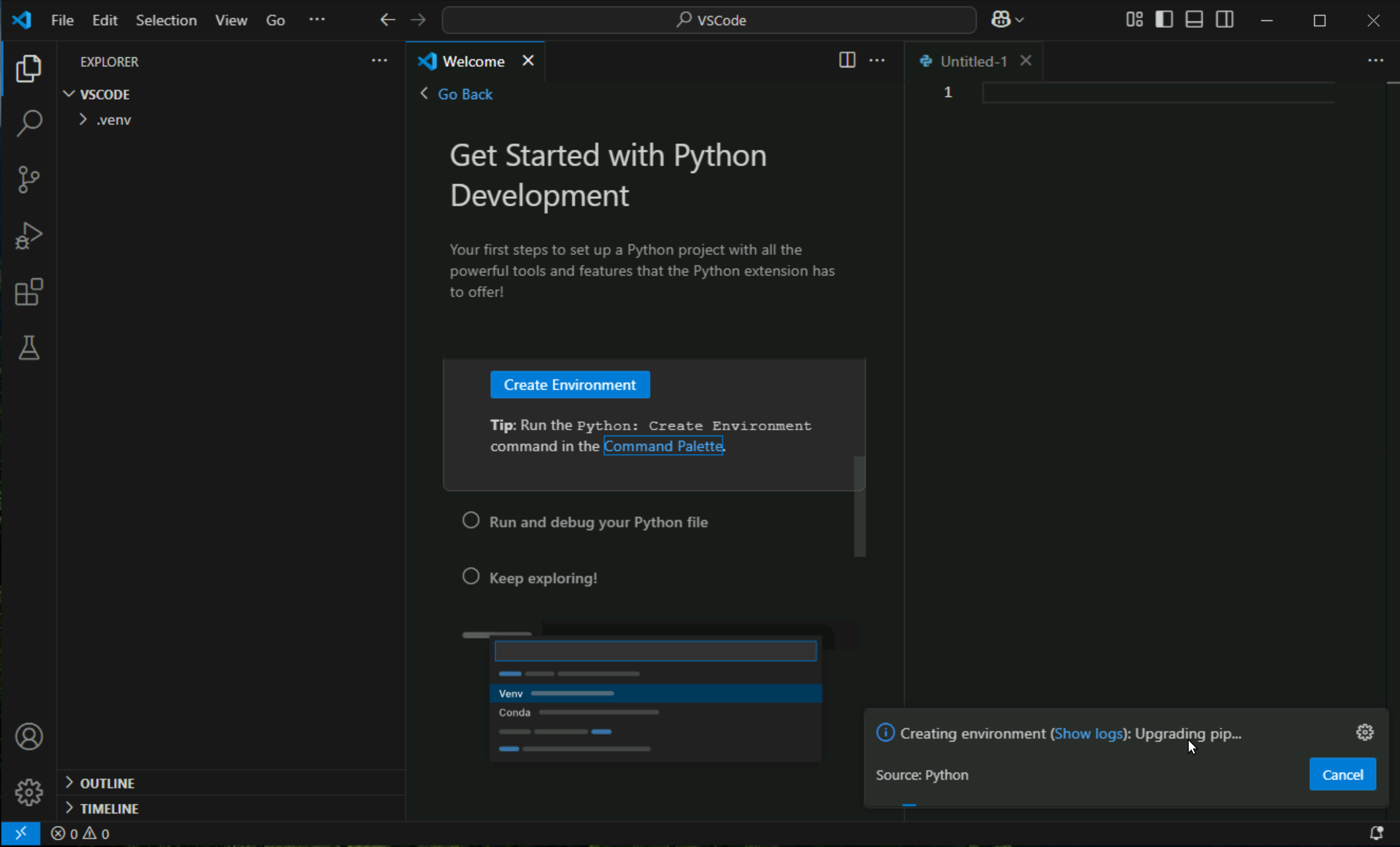

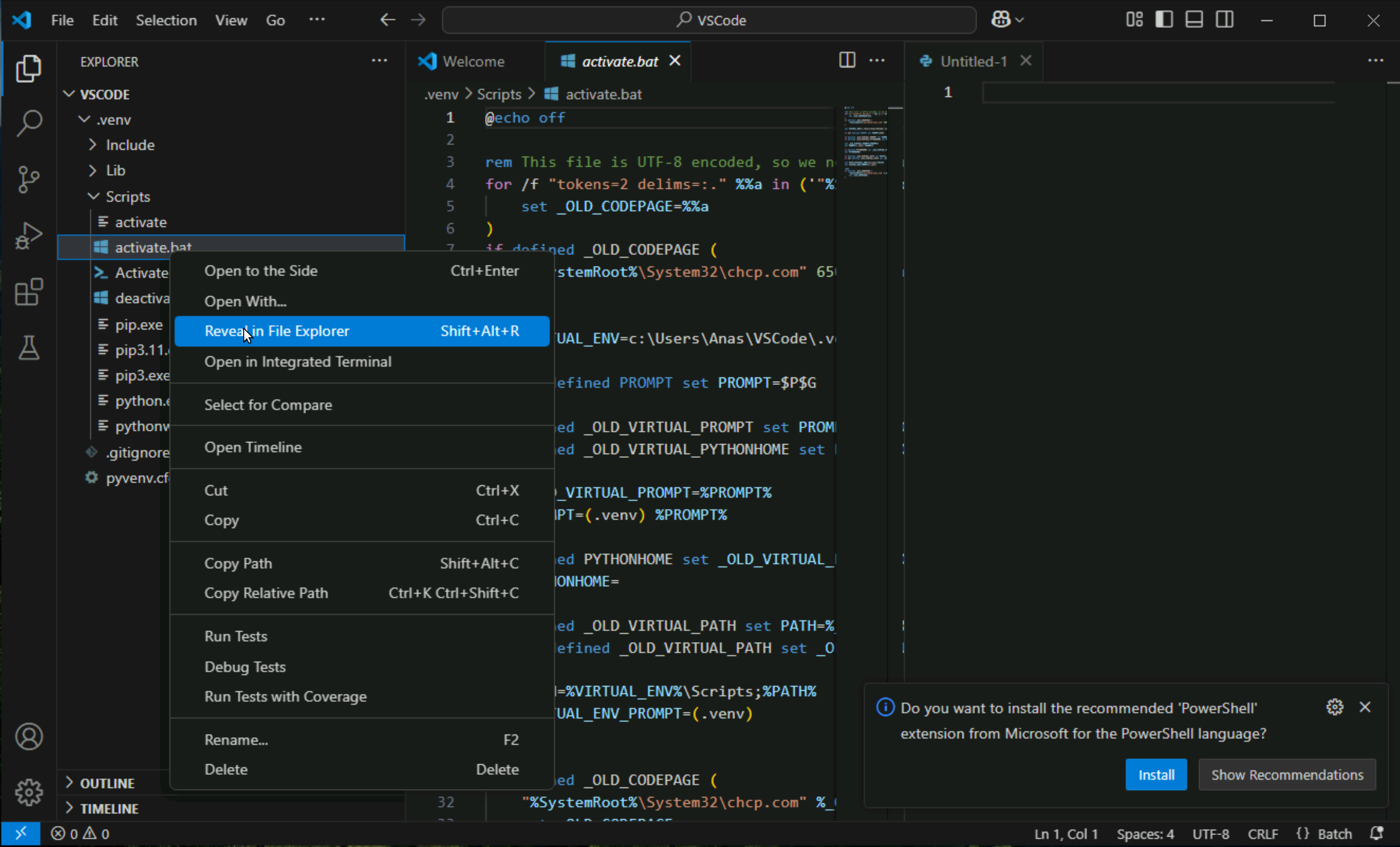

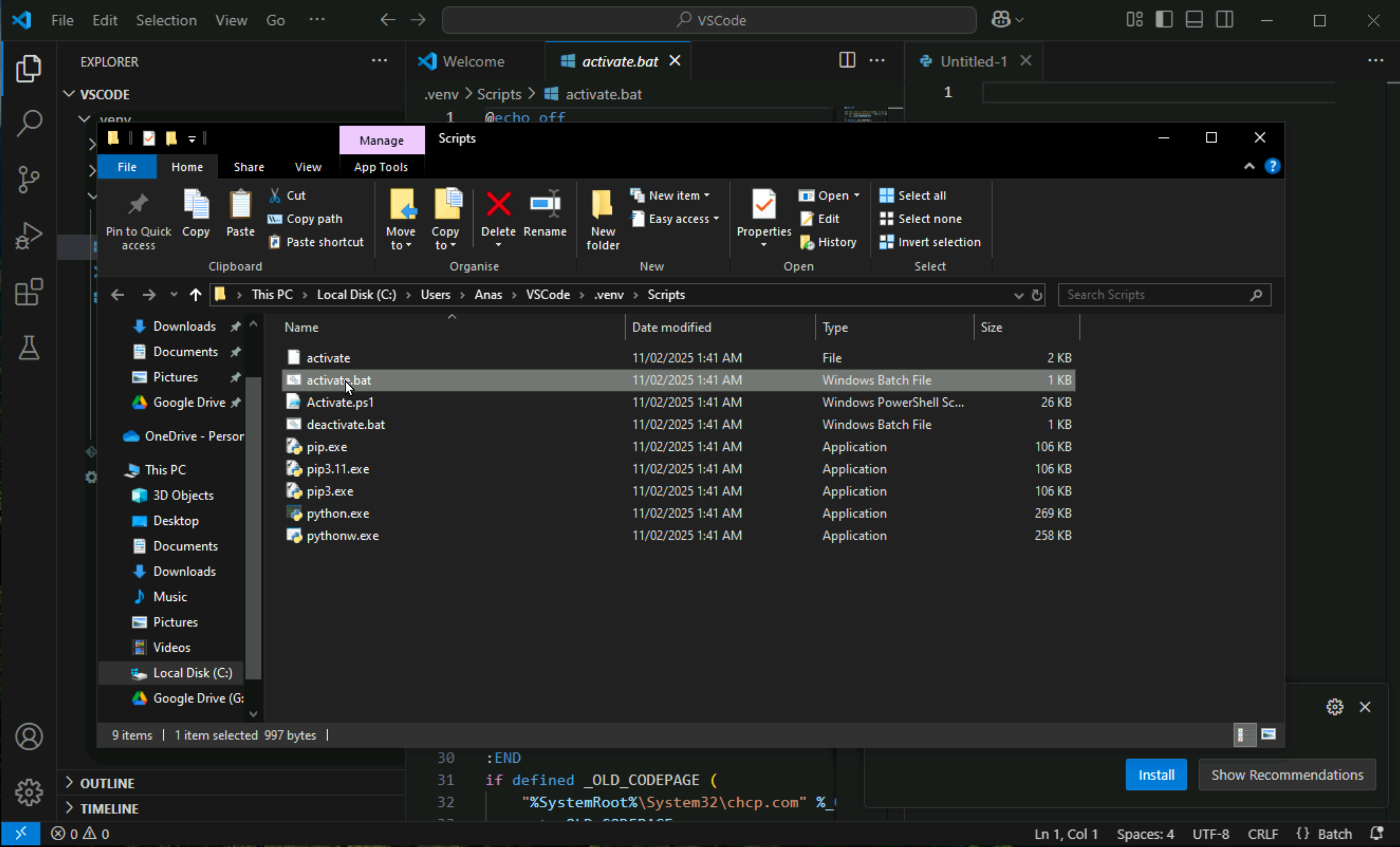

expand .venv and click on activate.bat > Reveal in File Explorer

Manually creating envrionement incase initial wizard does not allow or skips it

Create a virtual environment

A best practice among Python developers is to use a project-specific virtual environment. Once you activate that environment, any packages you then install are isolated from other environments, including the global interpreter environment, reducing many complications that can arise from conflicting package versions. You can create non-global environments in VS Code using Venv or Anaconda with Python: Create Environment.

Open the Command Palette (Ctrl+Shift+P), start typing the Python: Create Environment command to search, and then select the command.

The command presents a list of environment types, Venv or Conda. For this example, select Venv.

Click on activate.bat

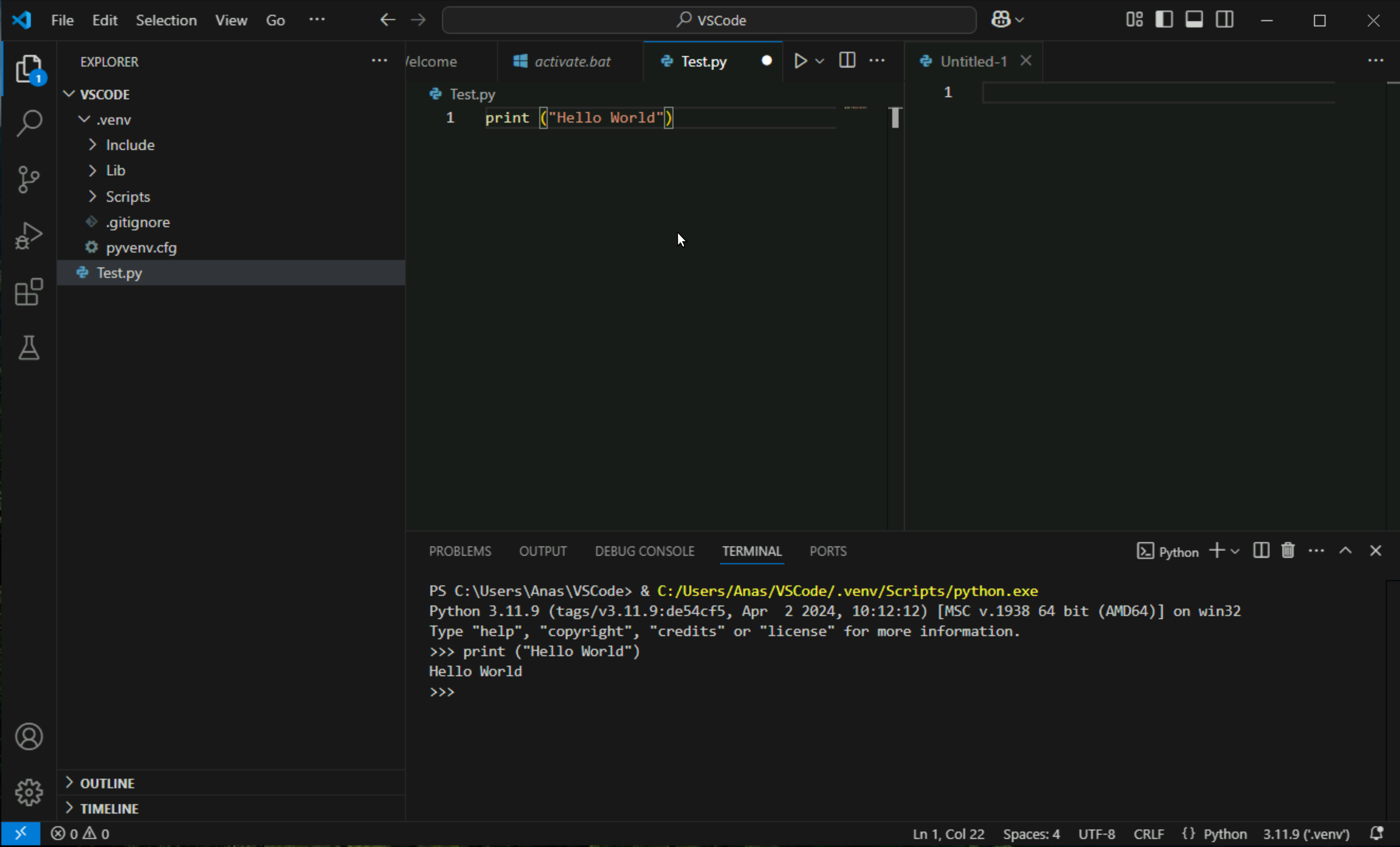

Click on empty space in explorer and click on new file, create a test python file as Test.py

Type some test code into it and press Shift + Enter to run this code

(Skip this) VSCode Extensions installation

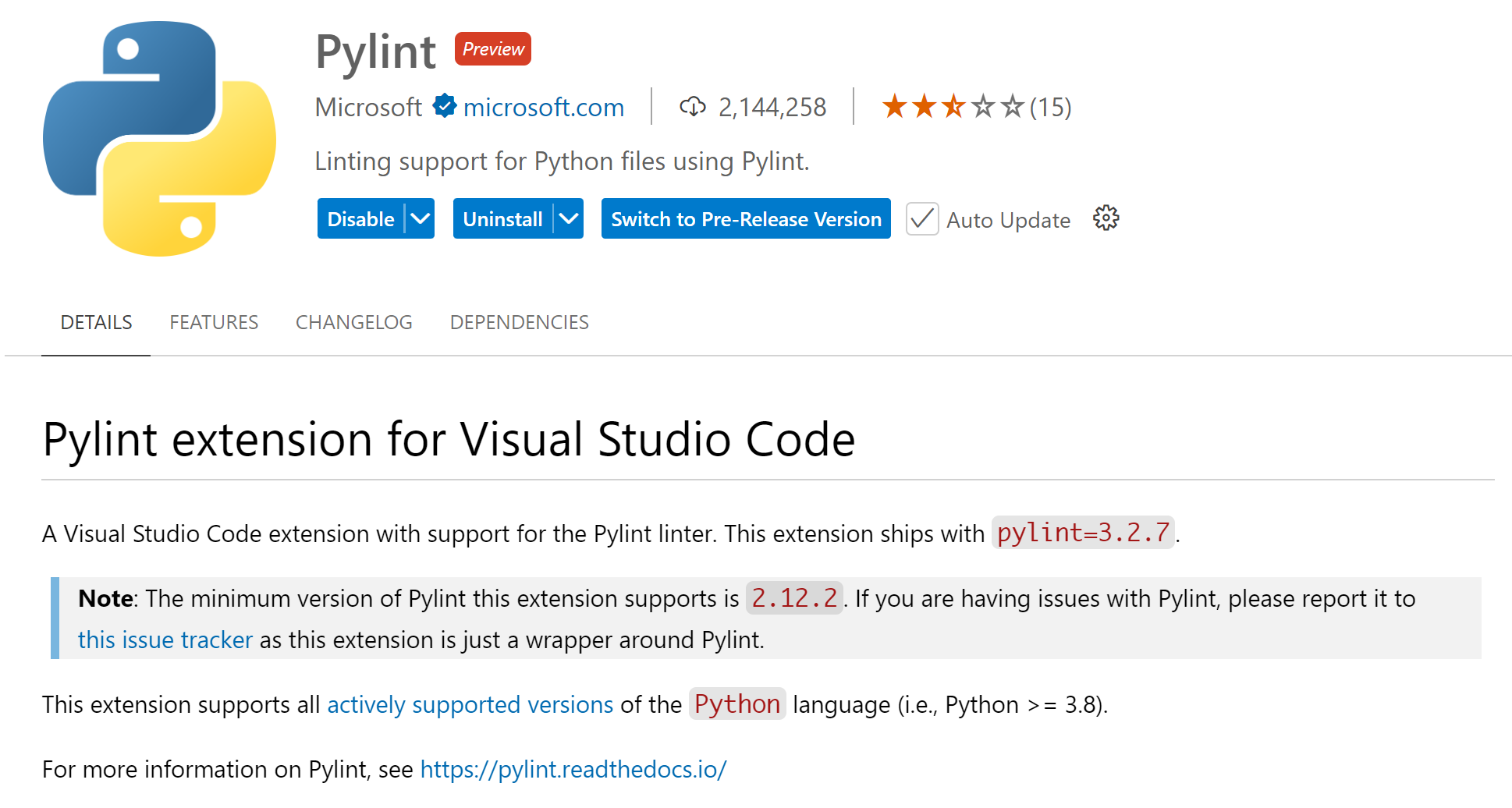

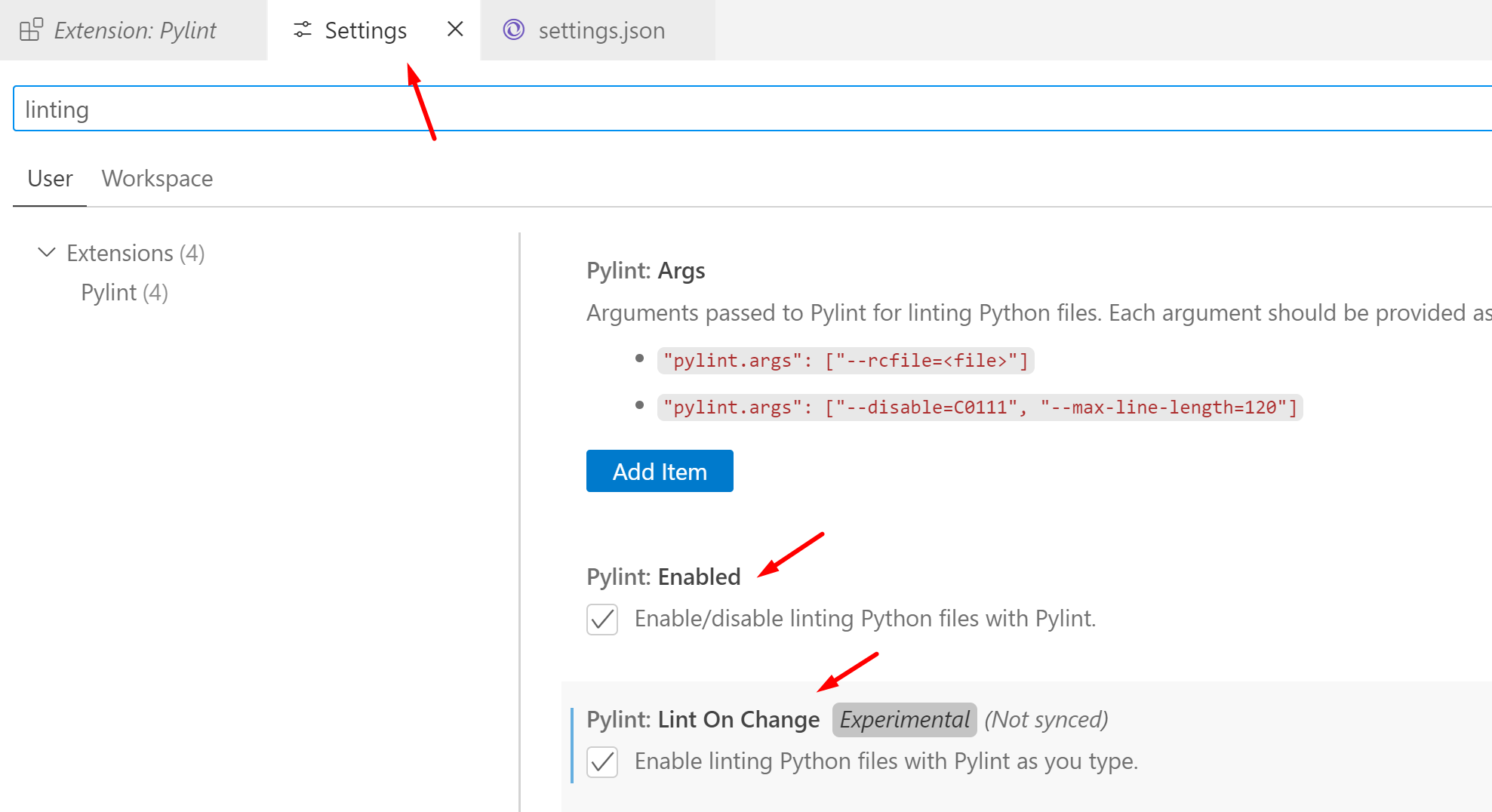

Pylint

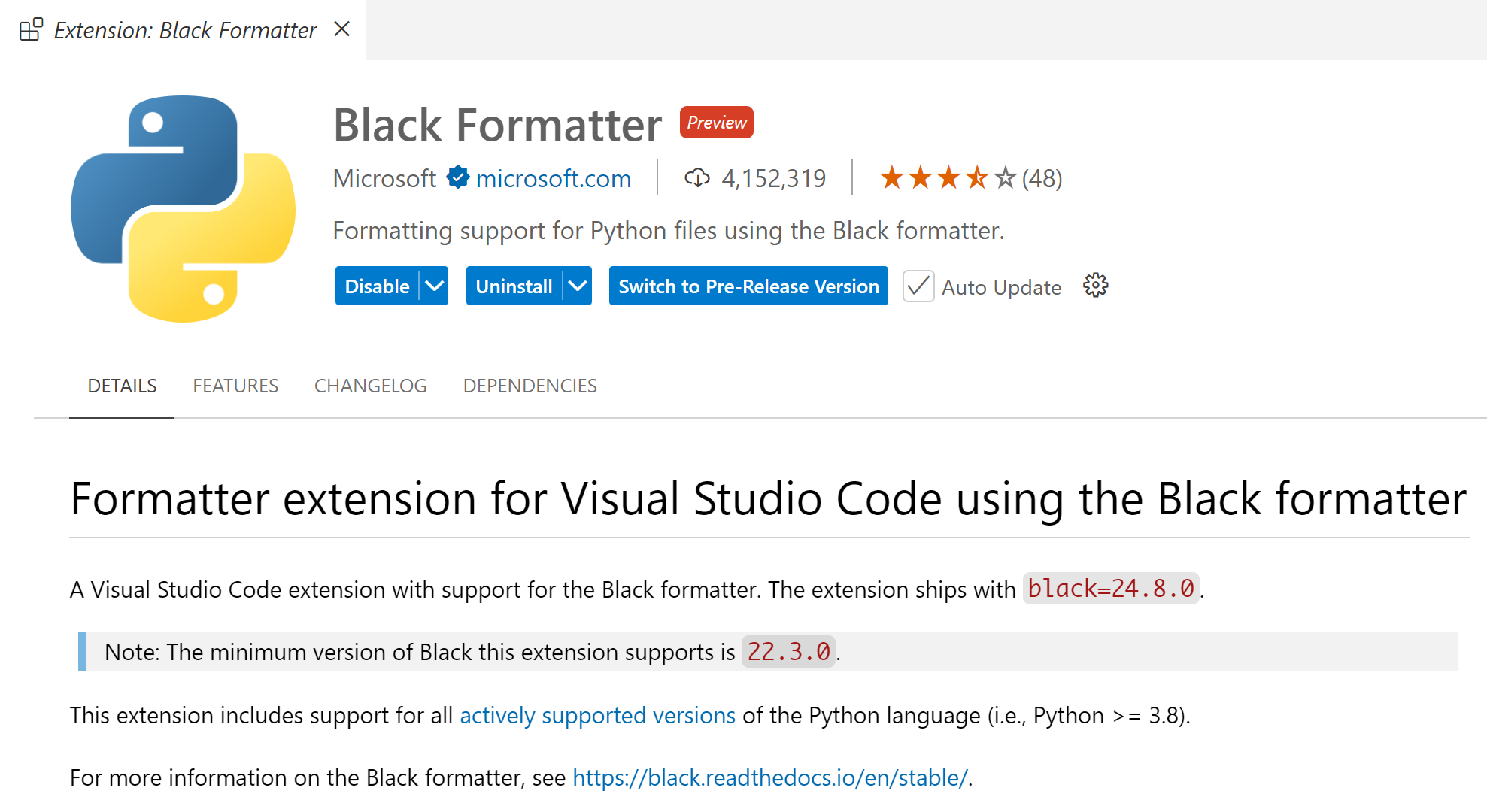

Black Formatter

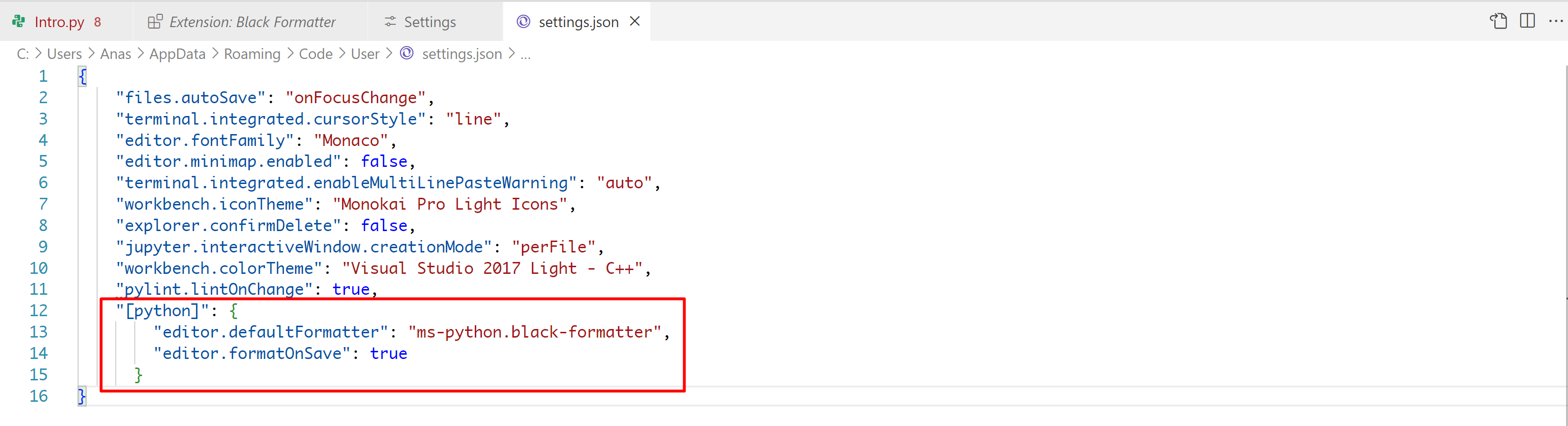

File > Preferences > Settings

open settings.json file by clicking on top

Add this line in settings.json

Environments

A Python environment is a container in which a Python runs. It consists of the Python interpreter (python.exe) and installed packages. There are different types of environments, but the most common ones are virtual environments.

Why Use Python Environments?

- Isolation: Each environment is isolated from others, meaning you can have different versions of Python and packages for different projects without conflicts. You dont really want to mix libraries between projects as it can increase code size of a particular project.

- Dependency Management: Helps manage dependencies for different projects, ensuring that each project has the correct versions of libraries it needs.

- Reproducibility: Makes it easier to reproduce the development environment on different machines, which is crucial for collaboration and deployment.

Types of Python Environments

- virtualenv:

- Creates isolated Python environments.

- Each environment has its own Python interpreter and libraries.

- Useful for managing dependencies for different projects.

- venv:

- A module that comes with Python 3.3 and later.

- Similar to

virtualenvbut included in the standard library.

- conda:

- A package and environment manager from Anaconda.

- Can manage environments and packages for Python as well as other languages.

- Useful for data science and machine learning projects.

Creating a Virtual Environment

python -m venv myenv

- is m is for manifest?

- This command creates a new directory called

myenvwhereever your cd is in CMD, containing a new Python environment.

This created myenv folder in User/Anas since CMD is cd there by default

Activating a Virtual Environment

- On Windows:

myenv\Scripts\activate.bat - On macOS and Linux:

source myenv/bin/activate --> that simple activate without extension is for linux and MacOS

Deactivating a Virtual Environment

To deactivate the environment, simply run:

deactivate.batvenv Environment created by Visual Studio Code for python

Sometimes running python in Visual studio runs it in and power shell says following

run following

Set-ExecutionPolicy -ExecutionPolicy Unrestricted -Scope LocalMachineVSCode reset keyboard shortcut to its defaults

- Click File > Preferences > Keyboard Shortcuts

- There is a triple-dot (…) at the top-right hand corner. Click on that and select “Show User Keybindings”

- Right click on the key-binding that you want to reset and choose “Reset Keybinding”

Run python script by pressing shift + enter

Open Command Palette (Ctrl+Shift+P or Cmd+Shift+P on Mac).

Search for: “Preferences: Open Keyboard Shortcuts (JSON)”.

Add this entry:

{

"key": "shift+enter",

"command": "python.execInTerminal",

"when": "editorTextFocus && editorLangId == 'python'"

},What are fields (attributes) in vscode?

In Python within VS Code, the term “fields” often refers to class attributes or instance attributes of a class.

- Class Attributes: These are variables defined directly within the class body, outside of any methods. They are shared among all instances of the class and their value stays same through out all instances

- Instance Attributes: Created at the time of instance being created, These are variables defined within the

__init__method (the constructor) or can be other methods of a class instance. They can be different or same for instances.

class MyClass:

class_attribute = "This is a class attribute" # Class attribute

def __init__(self, instance_value):

self.instance_attribute = instance_value # Instance attribute

working with self and init function just copy this line

def __init__("self, instance_value"):

and remove ", " and replace it with

".variablename ="

For example

self, instance_value

self.instance_attribute = instance_value

obj1 = MyClass("Value for obj1")

obj2 = MyClass("Value for obj2")

# Class attributes do not need to be defined at the time of object

# creation because they were already defined at the time of writing

# class

print(obj1.class_attribute) # Output: "This is a class attribute"

print(obj2.class_attribute) # Output: "This is a class attribute"

print(obj1.instance_attribute) # Output: "Value for obj1"

print(obj2.instance_attribute) # Output: "Value for obj2"In this example:

class_attributeare fixed and shared by bothobj1andobj2.instance_attributeis an instance attribute, and its value is different for each object.

f” {var} text ” – Easy formatting of text in print( )

a = "Hello"

b = "World"

print(f"{a} {b}")Easily print the variables along with string as single concatenated output by using short form of format function

Python code works inside { }

a = 5

b = 10

f"{a} plus {b} is {a + b}"

# 5 plus 10 is 15

# another example

def func1():

return f"""

{globals()}

"""

print(func1())

Self-Documenting f string f”{ variable= }”

number = 10

if number > 5:

raise Exception(f"The number should not exceed 5. ({number=})")

print(number)

Exception: The number should not exceed 5. (number=10)number=10 has come from code “number=” because this tells python to print the variable name and also its value after equals sign and even the object’s name and object content but only with f string, not with just the print function

user = 'eric_idle'

member_since = date(1975, 7, 31)

f'{user=} {member_since=}'

user='eric_idle' member_since=datetime.date(1975, 7, 31)immutable types

In Python, an immutable type is a type of object whose state or value cannot be changed after it is created or “not mutated”. Once an immutable object is created, any attempt to modify it will either result in an error or create a new object.

Common Immutable Types in Python:

- Integers (

int) - Floating-Point Numbers (

float) - Strings (

str) - Tuples (

tuple) - Frozen Sets (

frozenset) - Booleans (

bool)

x = 10

# remember that in python when we do x = 10, then x is not just x = 10 but x also becomes 10

print(id(x)) # Prints the memory address of x

x = x + 1

# that is why when we do x = x + 1, to python that looks like 10 = 10 + 1, but python still performs this operation by removing old x and by creating a new x and assign it 10 + 1, as python knows what programmer meant

print(id(x)) # A new memory address, showing that x now points to a new object

s = "hello"

print(id(s)) # Prints the memory address of the string "hello"

s = s + " world"

print(id(s)) # A new memory address, showing that s now points to a new objectt = (1, 2, 3)

print(id(t)) # Prints the memory address of the tuple, () is tuple

t = t + (4,)

# this is like adding two tuples together, here t is one tuple

# and (4,) is another tuple, just like x = x + 3 or s = s + " world!"

# this t + (4,) is another way of appending to a tuple

# because no changes are allowed in tuple since the creation

# of a tuple python creates a new tuple as tuple is immutable.

print(id(t))

# A new memory address, showing that t now points to a new objectvariables

x = "Name"

x = 10

# single line multiple declarations

x, y, z = 1, 2, 3

def func1():

a, b, c = 11, 22, 33string and range [x:x]

s = "Hello"

s = s + " world!"

print ("added two" + " lines together")

# string because is a list of characters

# individual letters can be accessed like below

somestring = "01234567890123456"

print(somestring[2])

print(somestring[0:15])

012345678901234

! 5 is not part of output but we expected it to be but it is not, end selector has last position but imagine that position to be occupied by our selector, and selection ends on one number before

somestring = "This is some string"

x = len(somestring) + 1

print(somestring[0:x])

# if we leave first number in range then it is

# considered 0 or beginning

somestring = "This is somestring"

print(somestring[:19])

# output

This is somestring

# if we leave the last or end of the range then it is

# considered end of the range

somestring = "This is somestring"

print(somestring[5:])

# output

is somestring

# if we leave both out then it is default as always

# will be considered to be 0 or start and end or last in range

somestring = "This is somestring"

print(somestring[:])

# output

This is somestring

# example of using negative range to access last item

print(list1[-1]) # will show the last item

# This is also a good way to access the last item

# in lists and tuples (not dictionarys)

list1 = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

list2 = list1[0:]

list3 = list1[:3]

list4 = list1[0:4]

list5 = list1[:]

print(id(list1))

print(id(list2))

print(id(list3))

# 2581915590720

# 2581915738496

# 2581915593600

# when a list is returned using range

# then it is a new list

# similarly tuples, when using range

# it will be a new tuple

tuple1 = (1, 2, 3)

tuple2 = tuple1[0:3]

tuple3 = tuple1[0:2]

print(id(tuple1))

print(id(tuple2))

print(id(tuple3))

# but see if full tuple is returned as tuple1

# then both refer to same object or memory location

# is same, this is same as x = 1, then y = x

# this is not true for the list, this is because

# lists are mutable and tuples are immutable

# output

# 2319082021888

# 2319082021888

# 2319082312000list, tuple, dictionary, set

list1 = [1, 2, 3]

! list resembles actual paper list []

tuple1 = (1, 2, 3)

! tuple resembles and sounds like a plant ()

dictionary1 = {"key1": "val1"}

! dictionary is represented by {} and "" which is very dictionary like

set1 = {"val1", "val2"}

! set contains only values and not they keys

print(dictionary1["key1"])

print(set1[1]) # this will give error

# set contains only values and not the keys

# since sets are unordered, they cannot

# be accessed with an index "[1]", but we

# can still loop through a set, once a set

# is created you cannot change its items but

# you can add new items

set1 = {1, 2, 3}

for val in set1:

print(val)

# 1

# 2

# 3print( )

print("this is line 1", "and this is same line")

print("this is line 1" + " and this is same line")

print("this is line 1" " and this is same line")

print("this is one line", end="\n")

print("this is line two", end="\n")

#output

this is one line

this is line two

print("This is one line", end=" ")

print("This is same line", end=" ")

#output

This is one line This is same line (.venv) admin@EVE2:~/vscode$

#output

this is one linethis is line two

this is one line this is line two

this is one line

this is line two

this is one line

this is line twofunctions

Some functions are built in which can be run as print( )

but some functions are coded into class / objects can be called after referencing object such as object.func( ) with a dot

def func2():

passimport

from ….. import …..

Using import python code in one module (a module is simply a python .py file) gains access to the code in another module (file), allowing you to reuse code while keeping your projects maintainable

Module is a single python code file (file with .py extension) while a package is a collection of modules (with a _init_.py file). Usually a module is imported using import command (import from either internal python library of code or from external packages installed) and packages are installed using pip

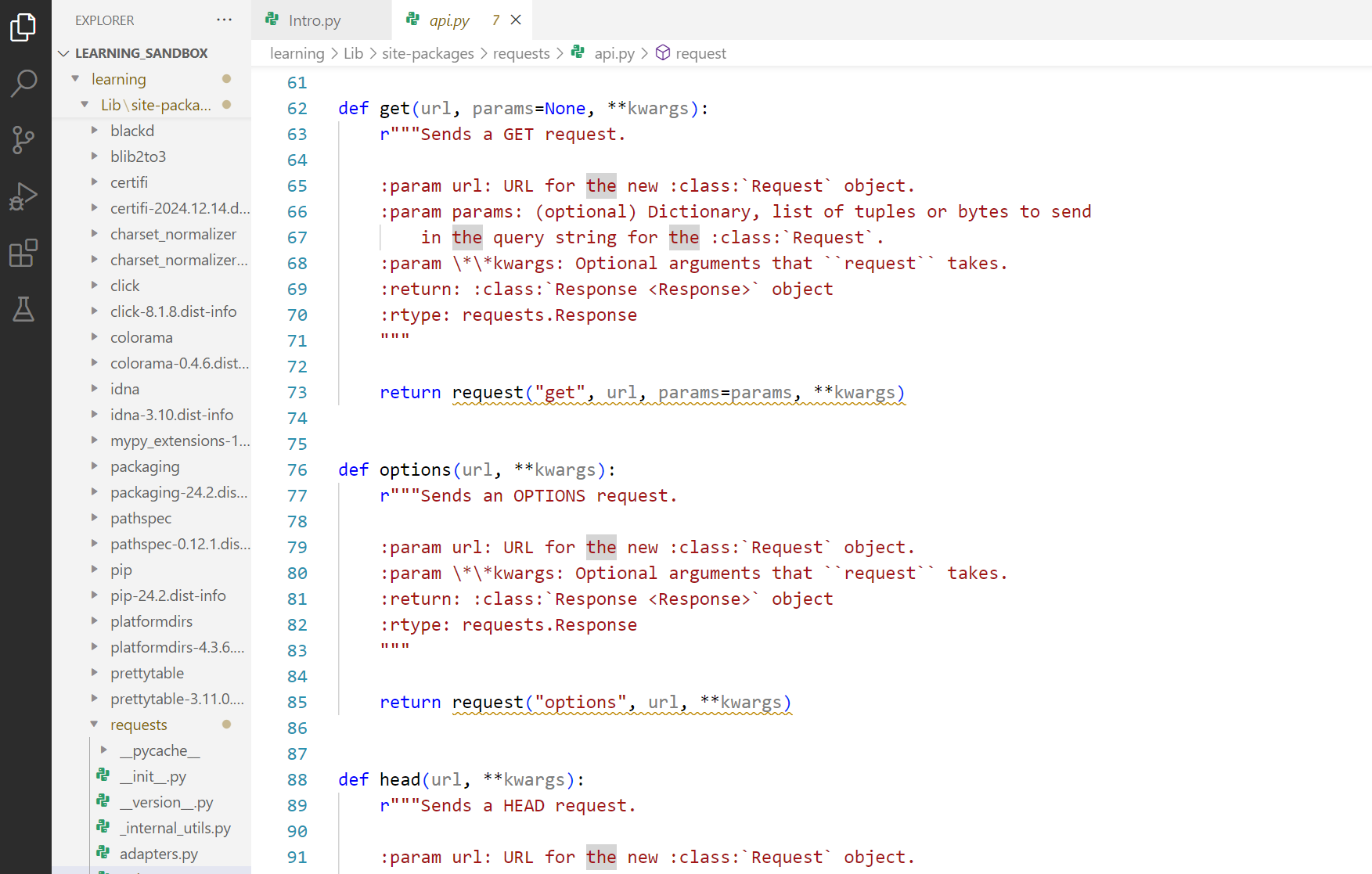

import requestsThis imports the entire requests “package”

“from” comes first then comes “import” because we are only importing small code from the package or module

from requests.auth import HTTPBasicAuth

| | |

| | |

folder | |

.py file in requests folder

|

class onlyfrom “Folder”.”file” import “class or any other piece of code”

or

from “file” import “class or any other piece of code”

This only imports single class (HTTPBasicAuth) from the requests.auth file, that is how requests package is designed, specific parts can be imported and used

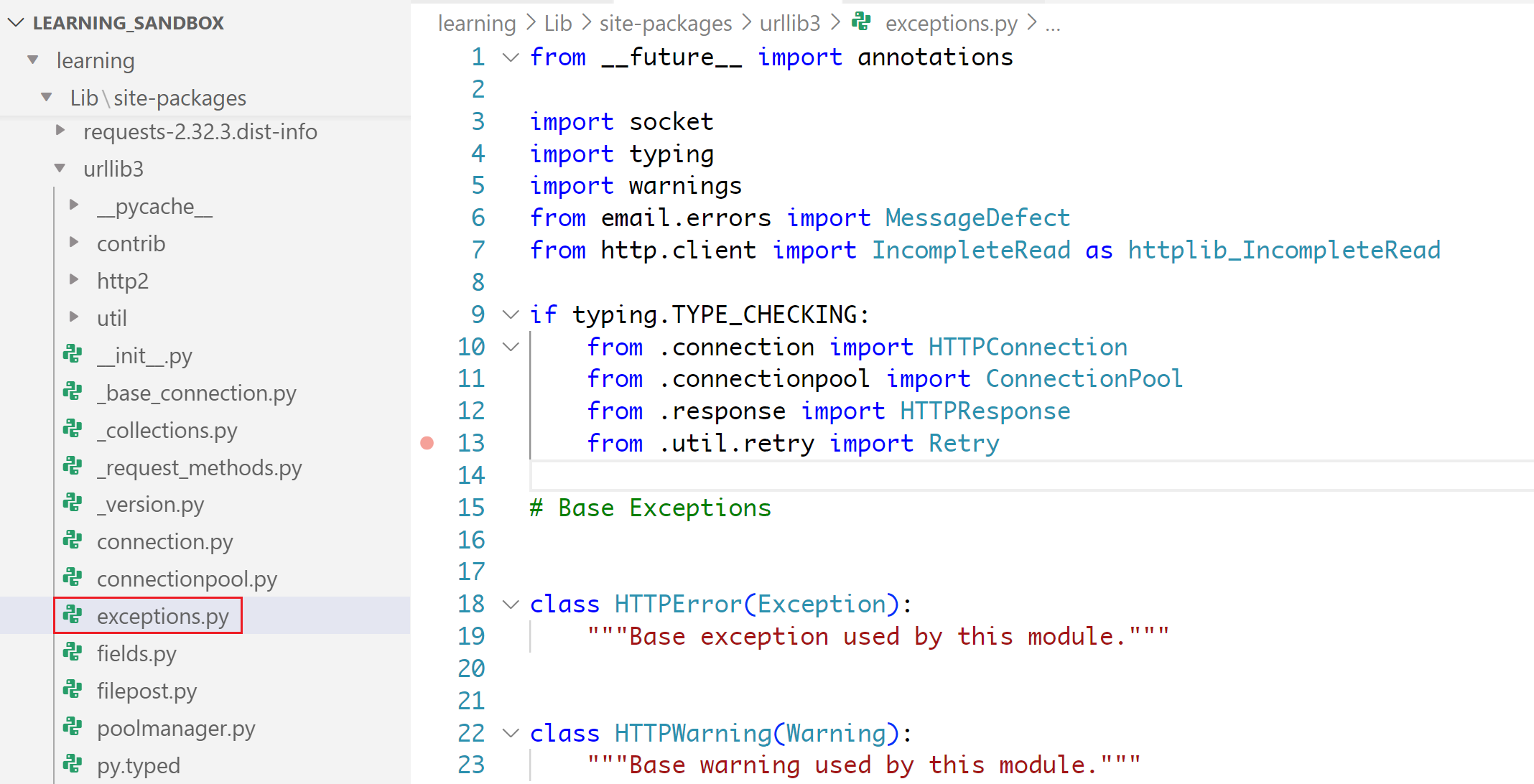

once import urllib3 is used we can use files under the folders as

# Silence the insecure warning due to SSL Certificate

urllib3.disable_warnings(urllib3.exceptions.InsecureRequestWarning)

| | |

| | |

Top Level Package Folder |

| |

.py file |

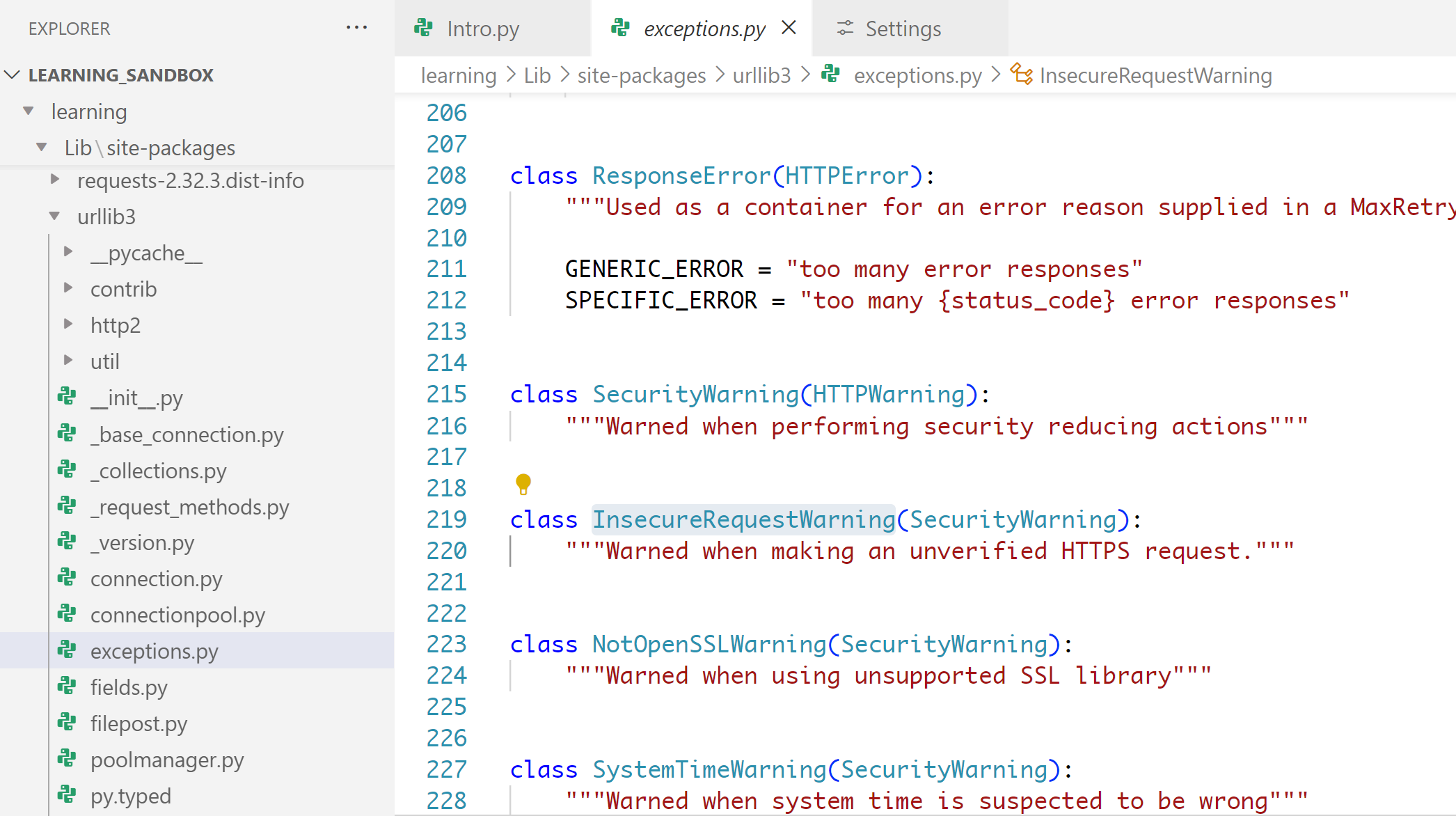

Class inside exceptions fileexceptions is a file inside the urllib3 package folder

InsecureRequestWarning is a class within this exceptions file

which is an empty class

from .api import delete, get, head, options, patch, post, put, request

# .api starts with dot because the file that is using api.py is in the same folder as api.py, The dot (.) signifies the current directory and package folder can be skipped in this case

# We can see that multiple functions from .api (.py) file have been imported

“From lets you import specific classes or functions or even variables or in general code section from a file in a package“

import: This keyword is used to bring in specific functions, classes, or variables from the specified file in the package into the current code and use it.

delete, get, head, options, patch, post, put, request: These are the specific functions being imported from the api.py file.

import json

# import JSON module so python can understand and work with JSON responses that are sent and received

import requests

# import requests module so python can handle HTTP headers

import urllib3

# import urllib3 which is a HTTP client

from requests.auth import HTTPBasicAuth

# imports HTTPBasicAuth method from the requests folder and auth file

# this class gives the ability to perform HTTP authentication to an HTTP server / website

from prettytable import PrettyTable

# Imports prettytable components from PrettyTable module to present returned data in table formatBeauty of imports is that you dont have to code HTTP headers mechanism from scratch but simply use requests

class

A class is makeup of an object, that you code before hand and use it by creating an instance.

Objects have member variables (attributes) and have functions (methods) associated with them

class Person:

person1 = Person("Alice", 30)

person1.introduce()type( ) – Finds type of an object using

Finds the type of the object

print(type(globals()))

#output

<class 'dict'>dictionary = { } – Remember { } and “” as this is frequently used in dictionary definition

Dictionaries are indexed by keys and not the index number like list and tuples are and you cannot skip defining keys, if you dont want to define keys then use something else and defined keys have to be unique

dictionary1 = {"1": "test", "two": "second-test"}

print(dictionary1[1])

# Traceback (most recent call last):

# File "g:\My Drive\0_Python\Projects\Learning_Sandbox\Intro.py", line 2, in <module>

# print(dictionary1[1])

# ~~~~~~~~~~~^^^

# KeyError: 1

# but if we define 1 as key in dictionary only then it will work

dictionary1 = {1: "test", "two": "second-test"}

print(dictionary1[1])

# testIt is best to think of a dictionary as a set of key: value pairs, with the requirement that the keys are unique (within one dictionary). A pair of braces { } creates an empty dictionary.

# define using curly braces

data_dct = {"name": "Alice", "age": 25, "city": "London"}

print(data_dct["name"]) # Output: Alice

# define using dict( ) function

data_dct = dict(name="Alice", age="30")

! using this method you dont have to use : and also dont have to "" the key names

# empty dictionary

data_dct = {}

# Changing values

data_dct["age"] = 28

# adding a new key value pair

data_dct["location"] = "Europe"

# clear all values using .clear( )

data_dct.clear()

print(data_dct)

# output

{}

# values, keys and items functions apply to the dictionary only

# because it is the only one with ability to store keys

# return all values using .values( )

values = data_dct.values()

# return all keys using .keys( )

keys = data_dct.keys()

# return all key value using .items( )

items = data_dct.items()

# checking a value using .get( ), returns none if values does not exist

age = data_dct.get("age")

# Removing Items using del and pop

del data_dct["city"]

age = data_dct.pop("age")

! assign and deleteNormal Iteration in dictionaries

data_dct = {

'name':'Anas',

'age':'31',

'profession':'Network Engineer',

'postcode':'IG3 8BD',

'car':'none',

'job status':'employed'

}

# Iterating in dictionary

# for loop gets keys only, not values

# for values we need to use a function

# .values()

for keys in data_dct:

print(f"{keys}: {data_dct[keys]}")

Getting values only using .values( )

data_dct = {

'name':'Anas',

'age':'31',

'profession':'Network Engineer',

'postcode':'IG3 8BD',

'car':'none',

'job status':'employed'

}

for key in dict_data:

print(key, dict_data[key])

for value in data_dct.values():

print(value)

print (data_dct.values())

# output

dict_values(['Anas', '31', 'Network Engineer', 'IG3 8BD', 'none', 'employed']Getting keys only using .keys( )

data_dct = {

'name':'Anas',

'age':'31',

'profession':'Network Engineer',

'postcode':'IG3 8BD',

'car':'none',

'job status':'employed'

}

for keys in data_dct.keys():

print(keys)

print(data_dct.keys())

# output

dict_keys(['name', 'age', 'profession', 'postcode', 'car', 'job status'])Iterate through keys and values using .items( )

data_dct = {"car": "Uber", "plane": "EasyJet"}

for key, value in data_dct.items(): # items() function allows keys with values in for

print(key, value)Nested Dictionaries

Persons = {

"Person1": {"Name": "person 1 ", "age": "33"},

"Person2": {"Name": "person 2 ", "age": "44"},

}

# 2 for loops will be needed

for key, val in Persons.items():

for key1, val1 in val.items():

print(f"{key1} \t {val1} \r\n")range( )

for i in range(5):

if i == 3:

continue #skip

print(i).items( )

items is a function that converts dictionary into a loopable list with key value tuple pairs

dict = {"car":"Uber", "plane":"737"}

print (dict) # This will print the entire dictionary as it is

print (dict.items()) # This will print a view object that displays a list of the dictionary’s key-value tuple pairs. This is mainly used in for loop

{'car': 'Uber', 'plane': '737'}

dict_items([('car', 'Uber'), ('plane', '737')])

^^ ^

|| |

[-----------------List----------------]

| |

(----Tuple---) |

(----Tuple---)

so this is a single List containing multiple Tuples of key and values

for loop looks at this as

[('car', 'Uber'), ('plane', '737')]

|

v

key value

| |

v v

('car', 'Uber')

('plane', '737')

for loop is passed a list

remember that anything that is passed to for loop is unpacked, so it unpacks list

and per pass for loop takes unpacked as below

key value

| |

v v

('car', 'Uber')

('plane', '737')

a good test is this code

# a list with tuples of 3 values

list1 = [

("key1", "value1", "metadata1"),

("key2", "value2", "metadata2"),

("key3", "value3", "metadata3"),

]

for first, second, third in list1:

print (first, second, third, end="\t")

print ("\r")

# output

key1 value1 metadata1

key2 value2 metadata2

key3 value3 metadata3

container = {

"key1":"value1",

"key2":"value2",

"key3":"value3",

"key4":"value4"

}

for keys, values in container.items():

print (keys, "\t", values, end="\r\n")

# same code can be written as

container_is_list = [

("key1", "value1"),

("key2", "value2"),

("key3", "value3"),

("key4", "value4"),

]

for keys, values in container_is_list:

print (keys, "\t", values)tuples = (1, 2)

Remember tuple from flower ( ), ( ) also looks like flower, may be remember tuple from tulips also

A tuple can store multiple items in a single variable, as it is not meant to be complicated, Tuples are immutable. Tuples are useful when you want data to never change. Tuples have advantage in being faster than lists for certain operations because of their immutability.

Ordered: The items in a tuple have a defined order, which will not change.

Unchangeable: Once a tuple is created, you cannot modify its items, you can’t add, remove, or change items to the tuple itself.

Allow Duplicates: Tuples can contain duplicate values.

Indexed: Each item in a tuple has an index, starting from 0.

Tuples are created by placing the items inside round parentheses ()

my_tuple = ("apple", "banana", "cherry")

print(my_tuple[1])

# Output: banana

# tuple short form like variable but with multiple quick values

my_tuple = 1, 2, 3

# empty tuple

empty_tuple = ()

# single value tuple

my_tuple = (5,)

mixed_tuple = ("abc", 34, True, 40.5)

If you want to create a tuple with only one item, you need to add a comma after the item:

single_item_tuple = ("apple",)

# comma is what actually defines the tuple, not the parentheses. Without the comma, Python would interpret the expression as a regular string enclosed in parentheses, rather than a tupleAppend to tuple

t = (1, 2, 3)

t = t + (4,)

# comma is what actually defines the tuple, not the parentheses. Without the comma, Python would interpret the expression as a regular number enclosed in parentheses, rather than a tupleConcatenation

tuple1 = (1, 2)

tuple2 = (3, 4)

result = tuple1 + tuple2 # Output: (1, 2, 3, 4)Repetition

repeated_tuple = (1, 2) * 3 # Output: (1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2)Slicing

tuple1 = (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

| | | x

include these

|

but end here and do not include it

print(tuple1[1:4])

# output

(1, 2, 3)

tuple1 = (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9)

# if i want 4, 5, 6

# count from where to start

# 4 is at the position 3

# and 7 is at position 6

print(tuple1[3:6])

# output

(4, 5, 6)

Common Use Cases:

Returning multiple values from a function:

def get_coordinates():

return (10, 20) # pass it as tuple

# assignment to variables from tuple

x, y = get_coordinates()As keys in a dictionary

dct = {('key1', 'key2'): 'value'}

# or

print({(1, 2): "key1 and 2"})

# output

{(1, 2): 'key1 and 2'}**kwargs

In Python, **kwargs is a special syntax used in functions to pass an undecided number of arguments. The term “kwargs” stands for “keyword arguments.”

When defining a function, you use **kwargs to allow the function to accept any number of keyword arguments. These arguments are passed as a dictionary where the keys are the argument names and the values are the argument values, useful when you want to create flexible functions that can handle a varying number of named arguments but name of the variables that are being passed in the function must have unique names among the variables.

def people (**kwargs):

for key, value in kwargs.items():

print (key, " ", value)

people (person1="Anas", person2="Mira")

# it will be wrong to repeat variable name person like below

# people (person="Anas", person="Mira")In this example, the function can accept any number of keyword arguments

def func_test(**kwargs):

pass

func_test(a=1)

# you cannot do func_test(1)Common Use Cases

- API Functions: Creating functions that can accept a wide range of parameters.

while loop

n = 0

while n < 5:

n += 1 ! remember to increment the condition as this is manual unlike for loop

if n == 3:

continue # skip

print(n)pass

The pass statement in Python is used as a placeholder for future code.

Here are some examples:

In a loop:

for i in range(5):

pass # Placeholder for future codeIn a function:

def my_function():

pass # Placeholder for future code In a class:

class MyClass:

pass # Placeholder for future codeIn an if statement:

if True:

pass # Placeholder for future codeUsing pass helps avoid syntax errors when you haven’t yet written the actual code

break

The break statement in Python is used to exit a loop early and exits the for or while loop

# break out of for loop

for i in range(5):

if i == 3:

break # exit if 3

print(i)

# break out of while loop

n = 0

while n < 5:

if n == 3:

break # exit if 3

print(n)

n += 1

continue

The continue statement in Python is used inside loops (like for and while) to skip the rest of the code for the current iteration and proceed directly to the next iteration of the loop

# continue in for loop

for i in range(5):

if i == 3:

continue #skip

print(i)

# continue in while loop

n = 0

while n < 5:

n += 1

if n == 3:

continue # skip

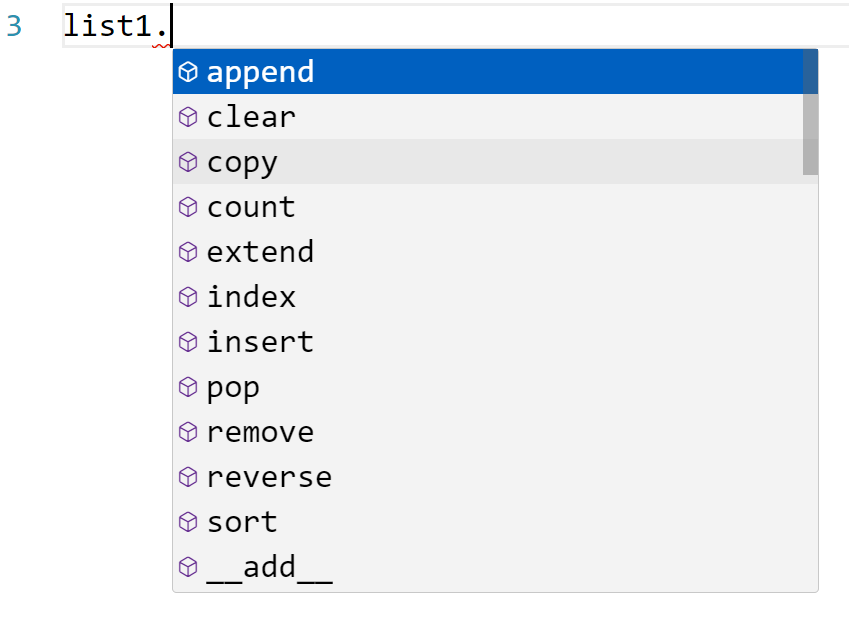

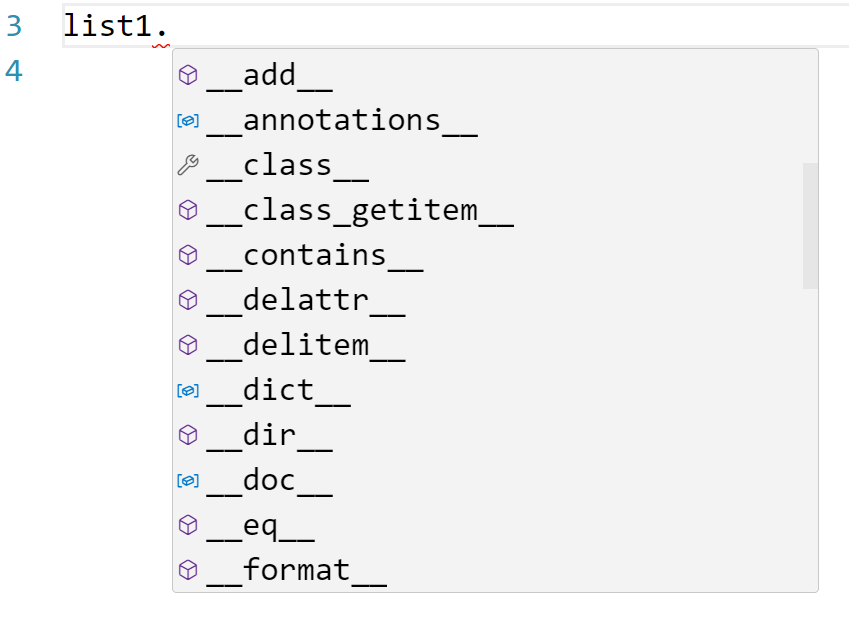

print(n).dir( )

The dir( ) function in Python is a built-in function used to list the variables (attributes) and methods of an object. Here’s a quick overview:

if no object is passed to dir( ) function then it lists the names in the current local scope

>>> print(dir())

['PS1', 'REPLHooks', '__annotations__', '__builtins__', '__doc__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__', 'get_last_command', 'original_ps1', 'sys']

# This will output the names of all the variables, functions, and imported modules in the current scope.

>>> globals () # this will show the content as well and not just the names

{'__name__': '__main__', '__doc__': None, '__package__': None, '__loader__': <_frozen_importlib_external.SourceFileLoader object at 0x000002A9582EBC50>, '__spec__': None, '__annotations__': {}, '__builtins__': <module 'builtins' (built-in)>, 'sys': <module 'sys' (built-in)>, 'original_ps1': '>>> ', 'REPLHooks': <class '__main__.REPLHooks'>, 'get_last_command': <function get_last_command at 0x000002A95889D260>, 'PS1': <class '__main__.PS1'>}Using dir( ) on a class:

>>> import math

>>> dir (math)

['__doc__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__', 'acos', 'acosh', 'asin', 'asinh', 'atan', 'atan2', 'atanh', 'cbrt', 'ceil', 'comb', 'copysign', 'cos', 'cosh', 'degrees', 'dist', 'e', 'erf', 'erfc', 'exp', 'exp2', 'expm1', 'fabs', 'factorial', 'floor', 'fma', 'fmod', 'frexp', 'fsum', 'gamma',

'gcd', 'hypot', 'inf', 'isclose', 'isfinite', 'isinf', 'isnan', 'isqrt', 'lcm', 'ldexp', 'lgamma', 'log', 'log10', 'log1p', 'log2', 'modf', 'nan', 'nextafter', 'perm', 'pi', 'pow', 'prod', 'radians', 'remainder', 'sin', 'sinh', 'sqrt', 'sumprod', 'tan', 'tanh', 'tau', 'trunc', 'ulp']

# This will output the attributes and methods of math classListing attributes of a list:

list1 = [1, 2, 3]

print(dir(list1))

['__add__', '__class__', '__class_getitem__', '__contains__', '__delattr__', '__delitem__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__getitem__', '__getstate__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__iadd__', '__imul__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__iter__', '__le__', '__len__', '__lt__', '__mul__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__reversed__', '__rmul__', '__setattr__', '__setitem__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', 'append', 'clear', 'copy', 'count', 'extend', 'index', 'insert', 'pop', 'remove', 'reverse', 'sort']

# This will show all the methods and attributes associated with a list object, such as append, remove, etc.Listing attributes of an object:

class MyClass:

def __init__(self):

self.name = "Python"

def greet(self):

return "Hello, " + self.name

obj = MyClass()

print(dir(obj))

['__class__', '__delattr__', '__dict__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__getstate__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__le__', '__lt__', '__module__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', '__weakref__', 'greet', 'name']This will list the attributes and methods of the MyClass instance, including __init__, greet, and name.

# you can also perform dir( ) on class as well as objects

print(dir(MyClass))The dir() function is particularly useful for introspection, allowing you to explore the capabilities of objects and modules in Python, but it does not differentiate between methods / functions and attributes / variables

dir() function lists all the attributes and methods of an object, but it doesn’t differentiate between them. To distinguish between attributes (variables) and methods (functions), you can use the getattr() function along with the callable() function

class MyClass:

class_attribute = "I am a class attribute"

def __init__(self, name) -> None:

self.name = name

def greet(self):

print(f"Hello {self.name}")

Anas = MyClass ("Anas")

Anas.greet()

all_attributes = dir(Anas)

attributes = []

for attr in all_attributes:

if not callable(getattr(Anas, attr)):

attributes.append(attr)

methods = []

for method in all_attributes:

if callable(getattr(Anas, method)):

methods.append(method)

print("Attributes:")

for attri in attributes:

print(attri)

print("----------------------------")

print("Methods:")

for meth in methods:

print(meth + "()")

# output

Attributes:

__dict__

__doc__

__module__

__weakref__

class_attribute

name

----------------------------

Methods:

__class__()

__delattr__()

__dir__()

__eq__()

__format__()

__ge__()

__getattribute__()

__getstate__()

__gt__()

__hash__()

__init__()

__init_subclass__()

__le__()

__lt__()

__ne__()

__new__()

__reduce__()

__reduce_ex__()

__repr__()

__setattr__()

__sizeof__()

__str__()

__subclasshook__()

greet()attributes

Attributes in a class are essentially variables that belong to the class and its instances. There are two main types of attributes in a class:

Instance Attributes

These are attributes that are specific or unique to instance only and are not shared among all instances. They are usually defined within the __init__ method and are accessed using the self keyword.

class MyClass:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name # Instance attribute

obj1 = MyClass("Alice")

obj2 = MyClass("Bob")

print(obj1.name) # Output: Alice

print(obj2.name) # Output: BobClass Attributes

These are attributes that are shared among all instances of the class. They are defined directly within the class, outside of any methods.

class MyClass:

class_attribute = "I am a class attribute" # Class attribute

# class attributes are backed into every object

# that is created from this class

# class attribute is like DNA

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name # Instance attribute

obj1 = MyClass("Alice")

obj2 = MyClass("Bob")

print(MyClass.class_attribute) # Output: I am a class attribute

print(obj1.class_attribute) # Output: I am a class attribute

print(obj2.class_attribute) # Output: I am a class attribute

Accessing Attributes

- Instance attributes are accessed using the instance name followed by a dot and the attribute name (e.g.,

obj1.name). - Class attributes can be accessed using the class name (e.g.,

MyClass.class_attribute) or through an instance (e.g.,obj1.class_attribute).

__init__ (self, value1, value2 … ):

class Person:

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

# like class attributes these variables are now defined

# use of self.name will create a variable inside the object

# self.name's self will also differentiate the argument's name

# with the object's name

# __init__ needs first argument as object and self is passed to it and "instance attributes"

def introduce(self):

print(f"Hello, my name is {self.name} and I am {self.age} years old.")

# Creating an instance of the Person class

person1 = Person("Alice", 30)

person1.introduce()

# another example

class person:

entity_type = "Human"

dimension = "3rd"

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def introduce(self) -> None:

print(

f"Hello my name is {self.name} and I welcome you to {self.dimension} dimension"

)

person1 = person("Anas")

person1.introduce()

# output

Hello my name is Anas and I welcome you to 3rd dimensionDouble underscore methods such as __init__ etc

>>> dir(Person)

['__class__', '__delattr__', '__dict__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__le__', '__lt__', '__module__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', '__weakref__', 'age', 'country', 'name']The names you listed with double underscores (__) are known as “dunder” (double underscore) methods or “magic” methods in Python. These methods are special methods that have specific meanings and are used to define the behavior of objects in Python. Here’s a brief overview of some of them:

__init__: Initializes a new instance of a class.__str__: Returns a string representation of an object.__repr__: Returns an official string representation of an object.__eq__: Defines the behavior for the equality operator==.__lt__: Defines the behavior for the less-than operator<.__dict__: A dictionary or other mapping object used to store an object’s (writable) attributes.__class__: References the class to which an instance belongs.

Namespaces, Scope & Variables

https://realpython.com/python-namespaces-scope

Symbolic names: when you create a variable x

x = ‘something’, you have technically created a symbolic name x that refers to string object ‘something’

In a program of any complexity, you’ll create hundreds or thousands of such names, each pointing to a specific object. How does Python keep track of all these names so that they don’t interfere with one another? Enter Namespaces, Namespaces can be thought of as a nested collections containing loads of <object names: object’s content>

Namespaces in Python

You can think of a namespace as a dictionary in which the keys are the object names and the values are the objects themselves, Each key-value pair maps a name to its corresponding object.

In a Python program, there are four types of namespaces:

- Built-In

- Global

- Enclosing

- Local

These have differing lifetimes. As Python executes a program, it creates namespaces as necessary and deletes them when they’re no longer needed. Typically, many namespaces will exist at any given time.

The Built-In Namespace

The built-in namespace contains the names of all of Python’s built-in objects. These are available at all times when Python is running.

You can list the objects in built-in namespace using following command

dir(__builtins__)

['ArithmeticError', 'AssertionError', 'AttributeError',

'BaseException','BlockingIOError', 'BrokenPipeError', 'BufferError',

'BytesWarning', 'ChildProcessError', 'ConnectionAbortedError',

'ConnectionError', 'ConnectionRefusedError', 'ConnectionResetError',

'DeprecationWarning', 'EOFError', 'Ellipsis', 'EnvironmentError',

'Exception', 'False', 'FileExistsError', 'FileNotFoundError',

'FloatingPointError', 'FutureWarning', 'GeneratorExit', 'IOError',

'ImportError', 'ImportWarning', 'IndentationError', 'IndexError',

'InterruptedError', 'IsADirectoryError', 'KeyError', 'KeyboardInterrupt',

'LookupError', 'MemoryError', 'ModuleNotFoundError', 'NameError', 'None',

'NotADirectoryError', 'NotImplemented', 'NotImplementedError', 'OSError',

'OverflowError', 'PendingDeprecationWarning', 'PermissionError',

'ProcessLookupError', 'RecursionError', 'ReferenceError', 'ResourceWarning',

'RuntimeError', 'RuntimeWarning', 'StopAsyncIteration', 'StopIteration',

'SyntaxError', 'SyntaxWarning', 'SystemError', 'SystemExit', 'TabError',

'TimeoutError', 'True', 'TypeError', 'UnboundLocalError',

'UnicodeDecodeError', 'UnicodeEncodeError', 'UnicodeError',

'UnicodeTranslateError', 'UnicodeWarning', 'UserWarning', 'ValueError',

'Warning', 'ZeroDivisionError', '_', '__build_class__', '__debug__',

'__doc__', '__import__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__',

'__spec__', 'abs', 'all', 'any', 'ascii', 'bin', 'bool', 'bytearray',

'bytes', 'callable', 'chr', 'classmethod', 'compile', 'complex',

'copyright', 'credits', 'delattr', 'dict', 'dir', 'divmod', 'enumerate',

'eval', 'exec', 'exit', 'filter', 'float', 'format', 'frozenset',

'getattr', 'globals', 'hasattr', 'hash', 'help', 'hex', 'id', 'input',

'int', 'isinstance', 'issubclass', 'iter', 'len', 'license', 'list',

'locals', 'map', 'max', 'memoryview', 'min', 'next', 'object', 'oct',

'open', 'ord', 'pow', 'print', 'property', 'quit', 'range', 'repr',

'reversed', 'round', 'set', 'setattr', 'slice', 'sorted', 'staticmethod',

'str', 'sum', 'super', 'tuple', 'type', 'vars', 'zip']If you look you will recognise some of the commonly used functions as well such as print etc.

The Python interpreter creates the built-in namespace when it starts up. This namespace remains in existence until the interpreter terminates.

The Global Namespace

The global namespace contains any names defined at the level of the main program. Python creates the global namespace when the main program body starts, and it remains in existence until the interpreter terminates. term global namespace.

globals()

# globals( ) function gets us objects inside global namespace as a dictionary

{'__name__': '__main__', '__doc__': None, '__package__': None, '__loader__': <_frozen_importlib_external.SourceFileLoader object at 0x000001B4289CBCB0>, '__spec__': None, '__annotations__': {}, '__builtins__': <module 'builtins' (built-in)>, '__file__': 'g:\\My Drive\\0_Python\\Projects\\Learning_Sandbox\\Intro.py', '__cached__': None}

for key, val in dict(globals()).items(): # 1

print(f"{key}: {val}")

# 1: dict() function was used to force copy of the globals

# because running code with 'for key, val in globals().items()'

# gives error message 'RuntimeError: dictionary changed size during iteration'Strictly speaking, this may not be the only global namespace that exists. The interpreter also creates a global namespace for any module that your program loads with the import statement.

The Local and Enclosing Namespaces

Every function creates its own local namespace which is destroyed when function returns or exits. The interpreter creates a new namespace whenever a function executes. That namespace is local to the function and remains in existence until the function terminates. If we call the function multiple times each call creates new local scope

You can also define one function inside another:

def f():

print("Start f")

def g():

print("Start g")

print("End g")

return

g()

print("End f")

return

f()

# output

Start f

Start g

End g

End fWhen the main program calls f( ), Python creates a new namespace for f( ). Similarly, when f( ) calls g( ), g( ) gets its own separate namespace. The namespace created for g( ) is the local namespace, and from the perspective of g( ) the namespace created for f( ) is the enclosing namespace.

Each of these namespaces remains in existence until its respective function terminates.

In fact inner_function can access variables from all parent function’s namespaces above it including:

Global Namespace: Variables defined at the top level of the script or module.

Built-in Namespace: Names preassigned in Python (like len, print, etc.)

inner functions codes can access outer scope objects or names but outer scope codes cannot access inner scope objects or names.

What if there are 3 nested functions?

Yes, in Python, the innermost function can access the variables and names defined in all enclosing functions, including the outermost function. This is due to the concept of closures and the scope chain.

Here’s an example with three nested functions:

def outer_function():

outer_variable = 'I am outer'

def middle_function():

middle_variable = 'I am middle'

def inner_function():

inner_variable = 'I am inner'

print(inner_variable) # Accessing local variable

print(middle_variable) # Accessing middle function variable

print(outer_variable) # Accessing outer function variable

inner_function()

middle_function()

outer_function()

# output

I am inner

I am middle

I am outer

# another example

x = "x defined in global"

print(f"calling from global: {x}")

print("----------------------")

def level1():

y = "y defined in level1()"

print(f"calling from level1(): {x}")

print(f"calling from level1(): {y}")

print("----------------------")

def level2():

z = "z defined in level2()"

print(f"calling from level2(): {x}")

print(f"calling from level2(): {y}")

print(f"calling from level2(): {z}")

print("----------------------")

level2()

level1()

# output

calling from global: x defined in global

----------------------

calling from level1(): x defined in global

calling from level1(): y defined in level1()

----------------------

calling from level2(): x defined in global

calling from level2(): y defined in level1()

calling from level2(): z defined in level2()

----------------------

# first level1() is called and then level2()

# as level2() is called inside level1()

# even because of order of code and indents it

# looks like level2() was called but that is not

# the case

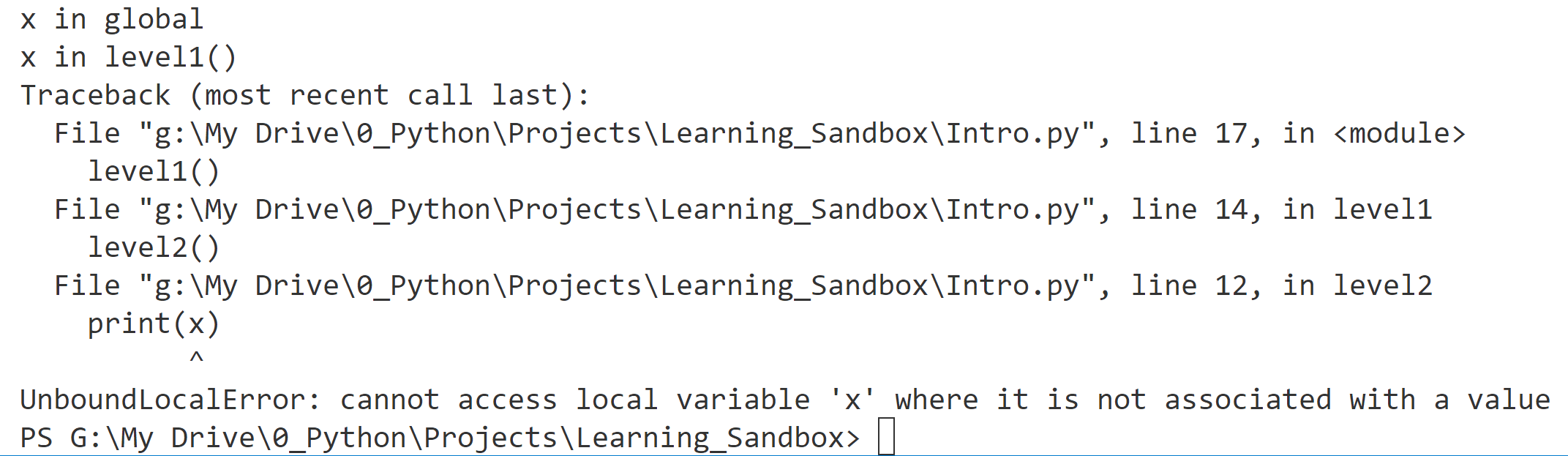

# another example

x = "x in global"

print(x)

def level1():

x = "x in level1()"

print(x)

def level2():

print(x) # 1

del x

print (x)

# error will happen because we deleted x in local scope

level2()

level1()

#1 If x is deleted then local scope will have no reference to x and above error will happen

# another example

x = "x in global"

print(x)

def level1():

x = "x in level1()"

print(x)

def level2():

print(x) # 1

level2()

level1()

x in global

x in level1()

x in level1()Variable Scope

The existence of multiple, distinct namespaces means several different instances of a particular name can exist simultaneously while a Python program runs. As long as each instance is in a different namespace, they’re all maintained separately and won’t interfere with one another.

But that raises a question: Suppose you refer to the name x in your code, and x exists in several namespaces. How does Python know which one you mean?

The answer lies in the concept of scope. The interpreter determines this at runtime

if your code refers to the name x, then Python searches for x in the following namespaces in the order shown (LEGB order):

- Local: If you refer to x inside a function, then the interpreter first searches for it in the innermost scope that’s local to that function.

- Enclosing: If x isn’t in the local scope but appears in a function that resides inside another function, then the interpreter searches in the enclosing function’s scope.

- Global: If neither of the above searches is fruitful, then the interpreter looks in the global scope next.

- Built-in: If it can’t find x anywhere else, then the interpreter tries the built-in scope.

This is the LEGB rule as it’s commonly called in Python literature

The interpreter searches for a name from the inside out, looking in the local, enclosing, global, and finally the built-in scope:

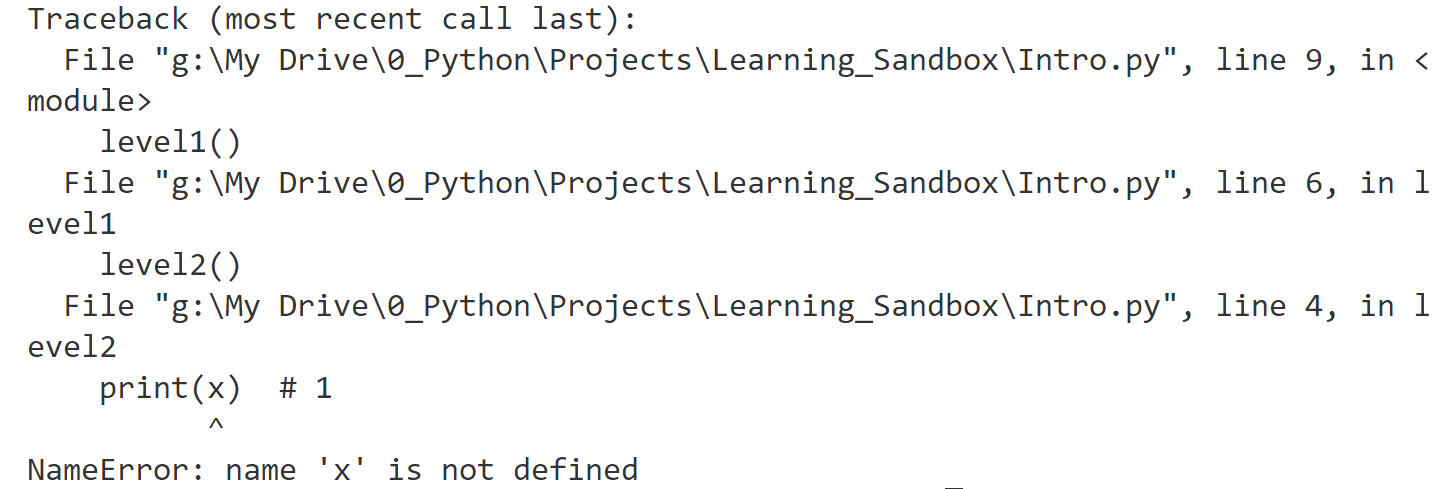

If the interpreter doesn’t find the name in any of these locations, then Python raises a NameError exception.

Single Definition

In the first example, x is defined in only one location, it resides in the global scope:

x = "global x"

def f():

def g():

print(x)

g()

f()

# output

global xDouble Definition

In the next example, the definition of x appears in two places

x = "global x"

def f():

x = "enclosing x"

def g():

print(x)

g()

f()

# output

enclosing xAccording to the LEGB rule, the interpreter finds the value from the enclosing scope before looking in the global scope. So the print() statement on line 7 displays ‘enclosing’ instead of ‘global’.

Triple Definition

n the next example, the definition of x appears in three places

x = "global x"

def f():

x = "enclosing x"

def g():

x = "local x"

print(x)

g()

f()

# output

local xHere, the LEGB rule dictates that g( ) sees its own local value of x first

No Definition

def level1():

def level2():

print(x)

level2()

level1()

Python Namespace Dictionaries

Earlier in this tutorial, when namespaces were first introduced, you were encouraged to think of a namespace as a dictionary in which the keys are the object names and the values are the objects themselves

In fact, for global and local namespaces, that’s precisely what they are! Python really implements these namespaces as dictionaries, the ones that are declared using { }, the only exception to this is __builtin__ namespace, __builtin__ doesn’t behave like a dictionary. Python implements it as a module, we will see that, it is eveident from the name __builtin__ that it is special

Python provides built-in functions called globals() and locals() that allow you to access global and local namespace dictionaries.

The globals( ) function

The built-in function globals() returns global namespace dictionary. You can use it to access the objects in the global namespace.

type(globals())

<class 'dict'>

globals()

{'__name__': '__main__', '__doc__': None, '__package__': None,

'__loader__': <class '_frozen_importlib.BuiltinImporter'>, '__spec__': None,

'__annotations__': {}, '__builtins__': <module 'builtins' (built-in)>}This is what is added by interpreter in globals namespace even before you have coded anything

now lets see what happens when we define a variable in the global scope:

x = 'foo'

globals()

{'__name__': '__main__', '__doc__': None, '__package__': None,

'__loader__': <class '_frozen_importlib.BuiltinImporter'>, '__spec__': None,

'__annotations__': {}, '__builtins__': <module 'builtins' (built-in)>,

'x': 'foo'}After the assignment statement x = ‘foo’, a new item appears in the global namespace dictionary.

If you are wondering why the contents of the module and class are not shown and just their description is shown, that is because it is easier to display small excerpt instead of long classes and modules, it can be seen that ‘x’ is the key in dictionary

Direct and Indirect access of the namespaces

You would typically access this object in the usual way, by referring to its symbolic name, x. But you can also access it indirectly through the global namespace dictionary:

x

# 'foo'

globals()['x']

# 'foo'

x is globals()['x']

# TrueThe is comparison confirms that these are in fact the same object. <namespace>( )[‘x’] can be used anywhere in code and objects inside that namespace can be accessed from anywhere indirectly even when there is no access to the namespace

You can create and modify entries in the global namespace using the globals() function as well as it is available for us to use and change just like any other dictionary:

globals()['y'] = 100

globals()

{'__name__': '__main__', '__doc__': None, '__package__': None,

'__loader__': <class '_frozen_importlib.BuiltinImporter'>, '__spec__': None,

'__annotations__': {}, '__builtins__': <module 'builtins' (built-in)>,

'x': 'foo', 'y': 100}

y

# 100

globals()['y'] = 3.14159

# notice that how we have to use ['y'] and not [y] because using [y] will result in this in globals dictionary: { 100: 3.14159 } which is valid as 100 can be key

y

3.14159The locals( ) function

Python also provides a corresponding built-in function called locals(). It’s similar to globals() but accesses objects in the local namespace instead:

def f(x, y):

a = "foo"

print(locals())

f(1, 2)

{'x': 1, 'y': 2, 'a': 'foo'}Notice that, in addition to the locally defined variable s, the local namespace includes the function parameters x and y since these are local to f() as well.

If you call locals() outside a function in the main program, then it behaves the same as globals(), because outside of the functions, locals ( ) will have same content as globals ( )

Deep Dive: A Subtle Difference Between globals() and locals() in same namespace level

globals() returns an actual reference to the dictionary that contains the global namespace, new variables will show up in the dictionary:

print(globals())

{'__name__': '__main__', '__doc__': None, '__package__': None, '__loader__': <_frozen_importlib_external.SourceFileLoader object at 0x0000018A7FCEBCB0>, '__spec__': None, '__annotations__': {}, '__builtins__': <module 'builtins' (built-in)>, '__file__': 'g:\\My Drive\\0_Python\\Projects\\Learning_Sandbox\\Intro.py', '__cached__': None}

x = "foo"

y = 29

print(globals())

{'__name__': '__main__', '__doc__': None, '__package__': None, '__loader__': <_frozen_importlib_external.SourceFileLoader object at 0x00000276F7AEBCB0>, '__spec__': None, '__annotations__': {}, '__builtins__': <module 'builtins' (built-in)>, '__file__': 'g:\\My Drive\\0_Python\\Projects\\Learning_Sandbox\\Intro.py', '__cached__': None, 'x': 'foo', 'y': 29}locals(), on the other hand, returns a dictionary that is a current “copy” of the local namespace, and not actual locals namespace like globals( ) function does

Changes in local namespace won’t update or effect previously stored copy until you call it again, because it was a true copy that was returned by locals( ) function

def f():

a = 1

local1 = locals()

print(local1)

a = 2

print(local1)

# still shows a = 1

print(locals()["a"])

# now it will show a = 2 as we got fresh copy

# by calling locals() again

f()

{'a': 1}

{'a': 1}

2Modify Variables Out of Scope

Situation exists when a function tries to modify a variable outside its local scope. A function can’t modify an immutable object outside its local scope at all:

x = 20

def f():

x = 40

print(x)

f() # 40

print(x) # 20When f() executes the assignment x = 40 on line 3, it creates a new local reference. At that point, f() loses the reference to the object named x in the global namespace. So the assignment statement doesn’t affect the global object. But after f() terminates, x in the global scope is still 20.

A function can “modify” an object of mutable type that’s outside its local scope

list1 = ["something", "is", "wrong"]

def change_list():

list1[1] = "is not"

change_list()

print(list1)

# output

['something', 'is not', 'wrong']But if f() tries to reassign my_list entirely, then it will create a new local object and won’t modify the global my_list:

list1 = ["something", "is", "wrong"]

def change_list():

list1 = ["something", "is", "off"]

print(list1)

change_list()

print(list1)

# output

['something', 'is', 'off']

['something', 'is', 'wrong']globals declaration

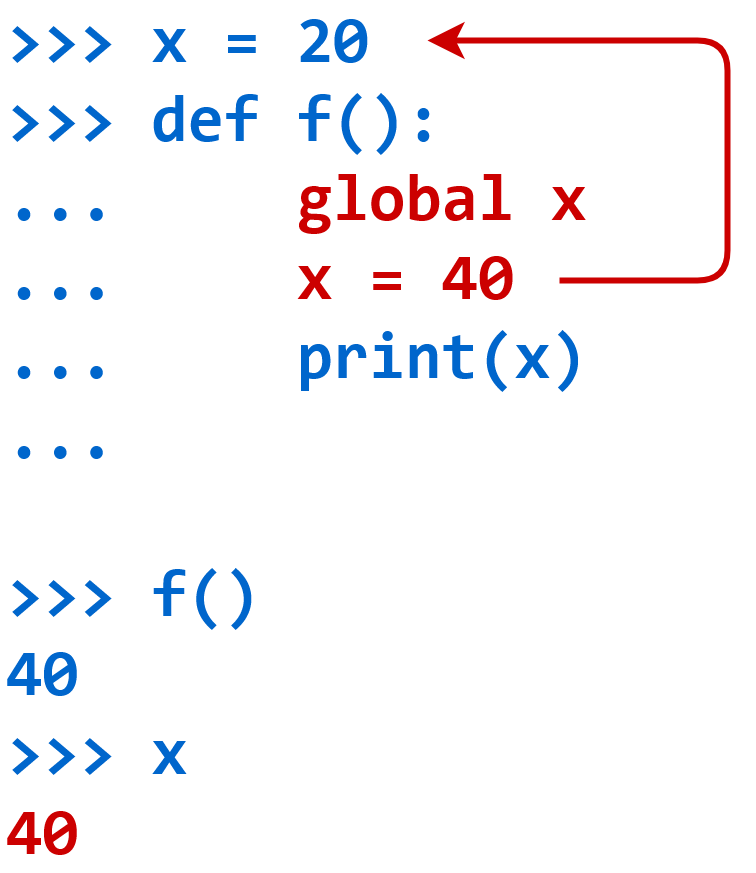

What if you really do need to modify a value in the global scope from within f()?

x = 20

def f():

global x #1

x = 40

print(x)

f()

print(x) #2

#1 global x declares that this x is same global x

#1 but this declaration must come on top inside the

#1 otherwise this error can be seen

def func1():

print(x)

del x

global x

x = 100

SyntaxError: name 'x' is used prior to global declaration

#2 global x was modified as expected Assignment x = 40 doesn’t create a new reference. It assigns a new value to x in the global scope

you could accomplish the same thing using globals() dictionary.

x = 20

def f():

globals()["x"] = 40

print(x)

f()

print(x)

# single line multiple declarations

# and declaring the global variables

# inside the function's namespace

x, y, z = 10, 20, 30

def f():

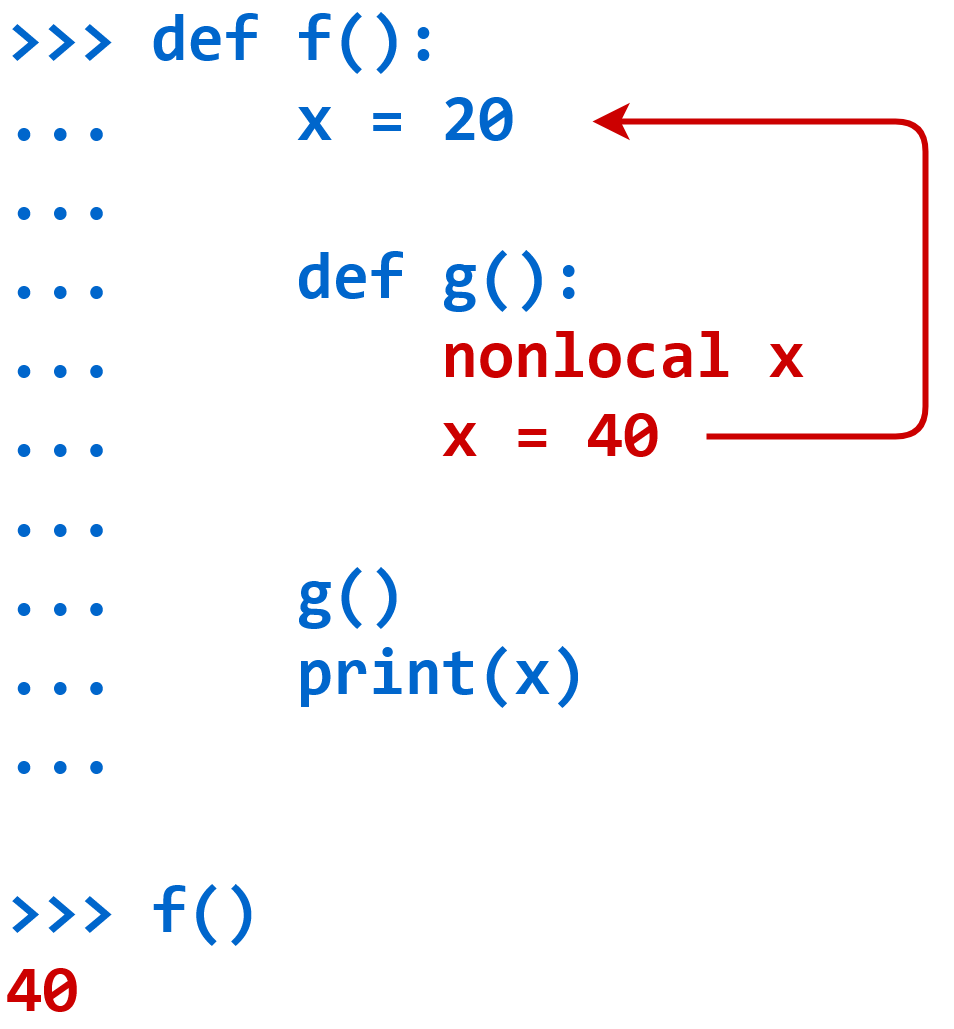

global x, y, zWhat if a function wants to modify values in enclosing or parent fucntion above it and not use global scope for setting and retrieving values

To modify variable in the enclosing scope from inside g(), you need the analogous keyword nonlocal. Names specified after the nonlocal keyword refer to variables in the nearest enclosing scope

def f():

x = 20

def g():

nonlocal x

x = 40

g()

print(x)

f()

# another example

def func1():

func1 = 111

def func2():

nonlocal func1

func1 = 222

func2()

print(func1)

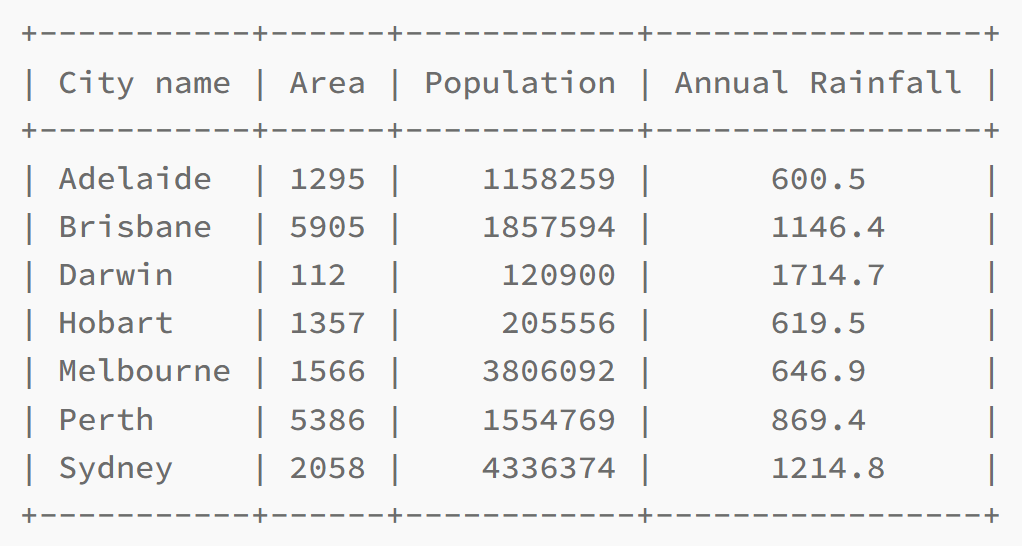

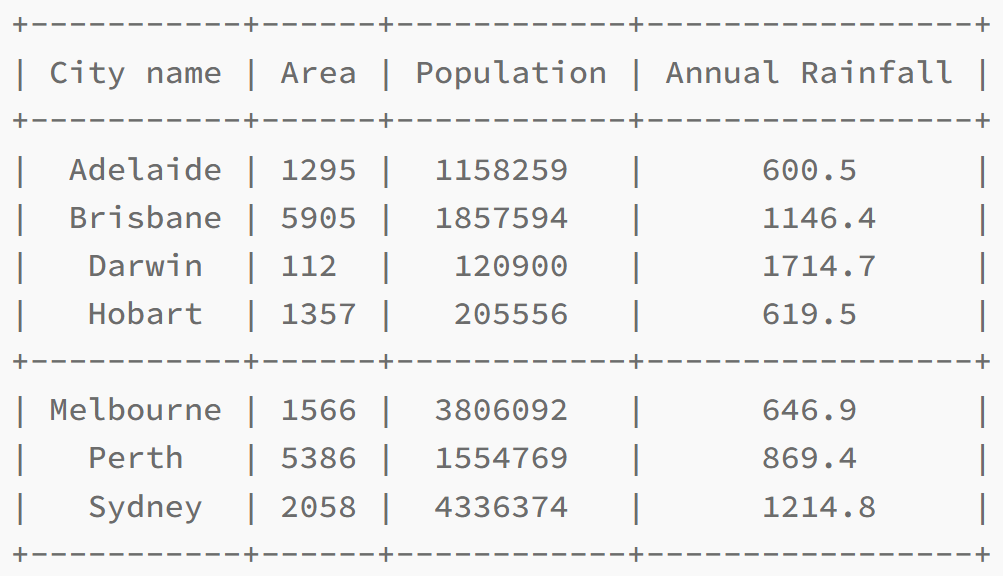

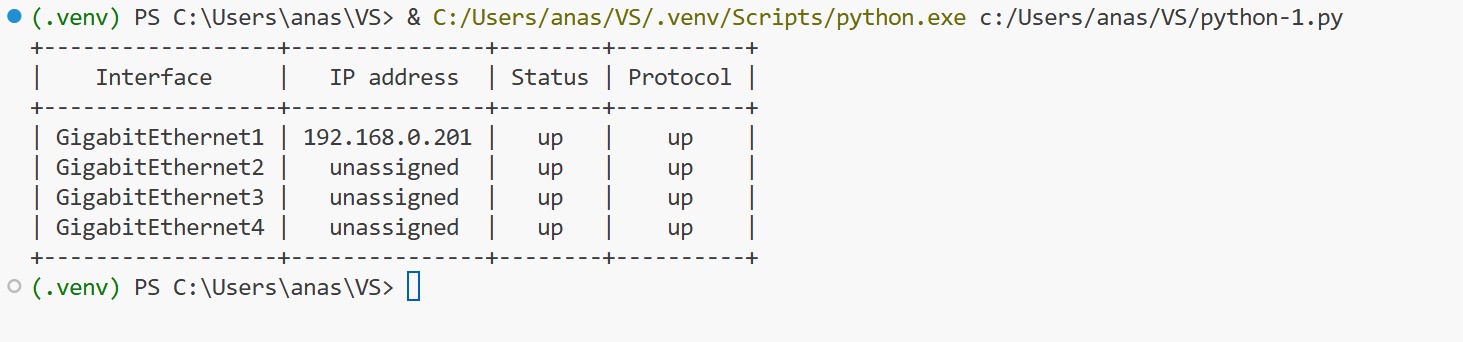

func1()prettytable

# install prettytable

pip install prettytable

from prettytable import PrettyTable

# Specify the Column Names while initializing the Table

# note that columns and rows are passed as one list as argument

# not as individual strings or variables

table1 = PrettyTable(["Name", "Class", "Section", "Percentage"])

or

table1 = PrettyTable()

table1.field_names = ["City name", "Area", "Population", "Annual Rainfall"]

table1.add_row(["Adelaide", 1295, 1158259, 600.5])

# Add rows

# if you do not pass values in the list that

# are equal to columns in the table, prettytable

# will error "Row has incorrect number of values, (actual) 1!=2 (expected)"

table.add_row(["Brisbane", 5905, 1857594, 1146.4])

table.add_row(["Darwin", 112, 120900, 1714.7])

table.add_row(["Hobart", 1357, 205556, 619.5])

print(table1)Pretty table requires lists while setting up column names and also when entering data such as add_row function, that also requires lists

you can simply print the table in the end

Adding data by column

You can add data one column at a time as well. To do this you use the add_column method, which takes two arguments – a string which is the name of the column and a list of data that should go in

table.add_column("City name",

["Adelaide","Brisbane","Darwin","Hobart","Sydney","Melbourne","Perth"])

# another example

table1 = PrettyTable()

table1.add_column("Attributes", attributes)

table1.add_column("Methods", methods)

print(table1)

# but doing this might cause this error since both columns are not

# of same size "ValueError: Column length 23 does not match number of rows 6"

Fix is to pad the smaller list with empty string to make it same size

from prettytable import PrettyTable

def show_attr_methods(object):

all_attributes = dir(object)

attributes = []

for attr in all_attributes:

if not callable(getattr(object, attr)):

attributes.append(attr)

methods = []

for method in all_attributes:

if callable(getattr(object, method)):

methods.append(method + "()")

if len(attributes) != len(methods):

print("both lists are not equals")

if len(attributes) > len(methods):

print(len(attributes) - len(methods))

for x in range(len(attributes) - len(methods)):

methods.append("")

elif len(attributes) < len(methods):

print(len(methods) - len(attributes))

for x in range(len(methods) - len(attributes)):

attributes.append("")

print(type(object))

table1 = PrettyTable()

table1.add_column("Attributes", attributes)

table1.add_column("Methods", methods)

table1.sortby = "Methods"

print(table1)

class person:

type = "Human"

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

Sorting

table.sortby = "Age"Alignment

table.align["Name"] = "l" # Left-align the 'Name' column

table.align["City"] = "r" # Right-align the 'City' columnAlignment of individual columns

table.align["City name"] = "l"

table.align["Area"] = "c"

table.align["Population"] = "r"

table.align["Annual Rainfall"] = "c"

print(table)

Border & Padding

table.border = False

table.padding_width = 2Adding sections to a table

table.add_row(["Hobart", 1357, 205556, 619.5], divider=True)

Deleting Rows

myTable.del_row(0)Clearing the Table

myTable.clear_rows()This will clear the entire table (Only the Column Names would remain).

Export to Other Formats

PrettyTable allows you to export tables to different formats such as HTML, CSV, or JSON:

# Export to HTML

print(table.get_html_string())

# Setting HTML escaping

# By default, PrettyTable will escape the data contained in the header

# and data fields when sending output to HTML. This can be disabled by

# setting the escape_header and escape_data to false. For example:

print(table.get_html_string(escape_header=False, escape_data=False))

# Export to CSV

print(table.get_csv_string())

# Export to JSON

print(table.get_json_string())Importing from CSV

from prettytable import from_csv

with open("myfile.csv") as fp:

mytable = from_csv(fp)Importing data from a database

import sqlite3

from prettytable import from_db_cursor

connection = sqlite3.connect("mydb.db")

cursor = connection.cursor()

cursor.execute("SELECT field1, field2, field3 FROM my_table")

mytable = from_db_cursor(cursor)Copying a table

new_table = old_table[0:5]list = [ ] – remember [] looks like a list

A Python list is a versatile and powerful data type used to store collections of items, it is like a tuple but values in positions can be changed. You can change, add, and remove items after the list has been created, while we cannot make changes on tuple, Lists can contain duplicate values.

Lists are created using square brackets [] which to be fair looks like a list itself, with items separated by commas, just like an array in PHP

my_list = ["apple", "banana", "cherry"]

# changing value on location 1

my_list[1] = "blueberry"

print(my_list) # Output: ["apple", "blueberry", "cherry"]Lists maintain the order of items. The first item has an index of 0, the second item has an index of 1, and so on.

print(my_list[0]) # Output: appleDuplicate values allowed

my_list = ["apple", "banana", "apple"]

print(my_list) # Output: ["apple", "banana", "apple"]A list can contain items of different data types, including strings, integers, and even other lists.

mixed_list = ["text", 123, True, [1, 2, 3]]

print(mixed_list) # Output: ["text", 123, True, [1, 2, 3]]Appending to list using append( ):

my_list.append("date")

print(my_list) # Output: ["apple", "banana", "cherry", "date"]Removing Items using remove( ):

my_list.remove("banana")

# directly reference the value to delete and not the key

print(my_list) # Output: ["apple", "cherry", "date"]

Length of List using len( ):

print(len(my_list)) # Output: 3

Slicing:

sub_list = my_list[1:3]

print(sub_list) # Output: ["cherry", "date"]Iterating through list

for item in my_list:

print (item)Keys are not part of the list but we can bring it using enumerate( ):

my_list = ["apple", "banana", "cherry"]

for index, value in enumerate(my_list):

print(f"Index: {index}, Value: {value}")Nested list loop

matrix = [

[1, 2, 3],

[4, 5, 6],

[7, 8, 9]

]

for row in matrix:

for value in row:

print(value, end=" ")

print() # Newline after each rowdel – delete objects

del is used to delete objects and any type of objects such as variables, lists, dictionary or its entries, and even entire objects, Frees up memory. Just like def, del is written as a construct, not as a function as it does not have ( ) parentheses.

Deleting a Variable

x = 10

print(x) # Output: 10

del x

print(x) # Raises NameError: name 'x' is not definedDeleting an Item from a List

my_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

del my_list[2]

print(my_list) # Output: [1, 2, 4, 5]Deleting a Slice from a List

my_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

del my_list[1:3]

# slice does not remove the last in range such as only my_list[1] and my_list[2] will be removed but not my_list[3], since position values start from 0

print(my_list)

#output: [1, 4, 5]

# another example

list1 = [1, 2, 3, 4, 44, 55, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

print(list1[4:6])

del list1[4:6]

print(list1)

Deleting a Dictionary Entry

my_dict = {'a': 1, 'b': 2, 'c': 3}

del my_dict['b']

print(my_dict) # Output: {'a': 1, 'c': 3}

Deleting an Object

class MyClass:

pass

obj = MyClass()

print(obj) # Output: <__main__.MyClass object at 0x...>

del obj

print(obj) # Raises NameError: name 'obj' is not definedid( )

The id() function in Python returns a unique identifier (memory address) for an object, You can use id() to check if two variables are pointing to the same object in memory, once an object is deleted using ‘del’ or any other way then that memory address or id can be reused by other objects

Basic Usage of id()

x = 10

y = 10

print(id(x)) # Prints the ID of the object 10

print(id(y)) # also prints the same id as x

# the reason they have same IDs is because of optimisation by python

# remember when we assign x = 10, x becomes 10

# and then when we assign y = 10, y also becomes 10

print (x == y) # True

print (id(x) == id(y)) # True

z = 20

print(id(z)) # Prints the ID of the object 20

Demonstrating Object Identity

x = [1, 2, 3] # this is a list

y = x # y points to the same list as x

# Same ID for both x and y

print(id(x))

print(id(y))

print(id(x) == id(y))

#output

True

y.append(4)

# Modifying y also modifies x because they refer to the same object as seen above that their memory address is same

print(x) # Output: [1, 2, 3, 4]

print(id(x) == id(y)) # True, they are still the same objectComparing Mutable and Immutable Types

x = [1, 2, 3]

y = [1, 2, 3]

# Different IDs because x and y are different objects

print(id(x))

print(id(y))

# different example

a = 42

b = 42

# Same ID because python optimizes by reusing objects

print(id(a))

print(id(b))len( )

my_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

# Count the size of the list

print (len(my_list))

# String

my_string = "Hello"

print(len(my_string)) # Output: 5

# Tuple

my_tuple = (1, 2, 3)

print(len(my_tuple)) # Output: 3

# Dictionary

my_dict = {"a": 1, "b": 2, "c": 3}

print(len(my_dict)) # Output: 3 (number of keys)

# Set

my_set = {1, 2, 3, 4}

print(len(my_set)) # Output: 4multiline comments

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/7696924/how-do-i-create-multiline-comments-in-python

“”” or ”’ is sometimes used for commenting and for multiline comments but in reality these are multiline strings and not the comments

'''

This is a multiline

comment.

'''

"""

This is a multiline

comment.

"""

I would advise against using """ for multi line comments!

Here is a simple example to highlight what might be considered an unexpected behavior:

print(

"This is one line",

"""

This is second line

but it is multiline

"""

"this is 3rd line",

)

Now have a look at the output:

This is one line

This is second line

but it is multiline

this is 3rd line

The multi line string was not treated as comment, but it was concatenated with next string

if you want to comment multiple lines, use # and in vscode use shortcut Ctrl + K Ctrl + C combination together and lines will be commented using #

if elif else

if True:

pass

x = 10

if x > 5:

print("x is greater than 5")

If with else

x = 3

if x > 5:

print("x is greater than 5")

else:

print("x is not greater than 5")

If with elif and else

x = 7

if x > 10:

print("x is greater than 10")

elif x > 5:

# elif comes first and then else comes in the end

# elif can not come after else

print("x is greater than 5 but less than or equal to 10")

else:

print("x is 5 or less")comparison operators

x == yinterpreter, simply enter object in interactive mode ‘>>>’

by simply entering the object’s name, the interpreter prints the object but first you have to create the object as interpreter instance when launched in interactive mode does not have your code so you have to create the object first

>>> x = 10

>>> x

10

.callable( )

xxxxxxx

.getattr( )

xxxxxxx

Helper code & tools

Print attributes and methods of the object in a prettytable

from prettytable import PrettyTable

def show_attr_methods(object):

all_attributes = dir(object)

attributes = []

for attr in all_attributes:

if not callable(getattr(object, attr)):

attributes.append(attr)

methods = []

for method in all_attributes:

if callable(getattr(object, method)):

methods.append(method + "()")

if len(attributes) != len(methods):

print("both lists are not equals")

if len(attributes) > len(methods):

print(len(attributes) - len(methods))

for x in range(len(attributes) - len(methods)):

methods.append("")

elif len(attributes) < len(methods):

print(len(methods) - len(attributes))

for x in range(len(methods) - len(attributes)):

attributes.append("")

print(type(object))

table1 = PrettyTable()

table1.add_column("Attributes", attributes)

table1.add_column("Methods", methods)

table1.sortby = "Methods"

print(table1)

class person:

type = "Human"

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = nameExample complex code stackoverflow

from prettytable import PrettyTable

def column_pad(*columns):

max_len = max([len(c) for c in columns])

for c in columns:

c.extend(['']*(max_len-len(c)))

# columns names

columns = ["Characters", "FFF", "Job"]

# lists

lista1 = ["Leonard", "Penny", "Howard", "Bernadette", "Sheldon", "Raj","Amy"]

lista2 = ["X", "X", "X", "X"]

lista3 = ["B", "C", "A", "D", "A", "B"]

column_pad(lista1,lista2,lista3)

# init table

myTable = PrettyTable()

# Add data

myTable.add_column(columns[0], lista1)

myTable.add_column(columns[1], lista2)

myTable.add_column(columns[2], lista3)

print(myTable)*args

In Python, the *columns syntax in a function definition indicates that the function can accept a variable number of positional arguments, which are collected into a tuple

the columns parameter will hold all the arguments passed to the function as a tuple

You can pass zero or more arguments to the function.

def column_pad(*columns):

max_len = max([len(c) for c in columns])

for c in columns:

c.extend(['']*(max_len-len(c)))

column_pad(lista1,lista2,lista3)

# another example

def args1(*values):

print(values) # 'values' is a tuple containing all the passed arguments.

args1("val1", "val2", "val3")

('val1', 'val2', 'val3')list comprehensions

List comprehensions are a powerful, they can generate list and also at the same time apply an expression to each element in iterable fashion for optional filtering. This simplifies and reduces code that would have required multiple lines of loop and conditions.

[expression for item in iterable (optional if_condition)]expression: This is the value that will go as a value in the new list.item: The current element being iterated over from theiterable.iterable: The source collection (e.g., a list, tuple, range, set, or generator) to iterate over.if_condition(optional): A filter that specifies which elements from theiterablewill be included.

How It Works

- The

iterableis iterated through one element at a time. - Each

itemis evaluated against theif condition(if provided). - The

expressionis applied to each validitem, and the result is added to the output list.

so we can read this in reverse by reading it from “for x in list1” then “if condition” if it exists and then expression which will be the value that new list will be populated with

# traditional code

square = []

for num in range(5):

square.append(num)

print(square)

# list comprehension

del square

square = [num for num in range(5)]

# | |

# | |

# num is what will be individual values in

# list so we will just use 'num'

# |

# |

# for loop start

print(square)

# list comprehension with if condition

evens = [num for num in range(0, 10) if num % 2 == 0]

print(evens)

# nested compression

pairs = [(x, y) for x in range(1, 2) for y in (33, 44)]

print(pairs)casting

# casting

# integers

x = int(1) # 1

y = int(2.8) # 2

z = int("3") # 3

# floats

x = float(1) # 1.0

y = float(2.8) # 2.8

z = float("3") # 3.0

w = float("4.2") # 4.2

# strings

x = str("s1") # s1

y = str(2) # 2

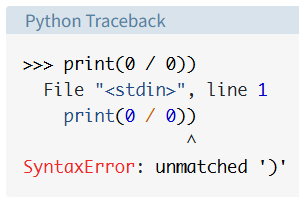

z = str(3.0) # 3.0Exception Handling

https://realpython.com/python-exceptions/

Python exceptions provide a mechanism for handling errors that occur during the execution of a program, Unlike syntax errors, which are detected by the parser (like when indentation is wrong or you missed a brace or parenthesis)

Knowing how to raise, catch, and handle exceptions is key to programming an error safe program

Arrow indicates that there was error syntax message, but if we run a code that is correct on syntax but has an issue with logic

>>> print(0 / 0)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ZeroDivisionError: division by zeroPython details what type of exception error it encountered. It was a exception of type ZeroDivisionError.

Python comes with various built-in exceptions as well as user-defined exceptions which users can create as well

You can also “raise” exception manually because exceptions are handled at the end of the program and not just for logical errors in python that was raised by Puthon Interpreter but you can also raise exceptions for your own program’s logic

Assume that you’re writing a tiny toy program that expects only numbers up to 5. You can raise an error when an unwanted condition occurs:

number = 10

if number > 5:

raise Exception(f"The number should not exceed 5. ({number=})")

print(number)Traceback (most recent call last):

File "./low.py", line 3, in <module>

raise Exception(f"The number should not exceed 5. ({number=})")

Exception: The number should not exceed 5. (number=10Note that the final call to print() never executed, because Python raised the exception before it got to that line of code. which means that code execution stops upon encountering an exception.

With the raise keyword, you can raise any exception object in Python and stop your program when an unwanted condition occurs

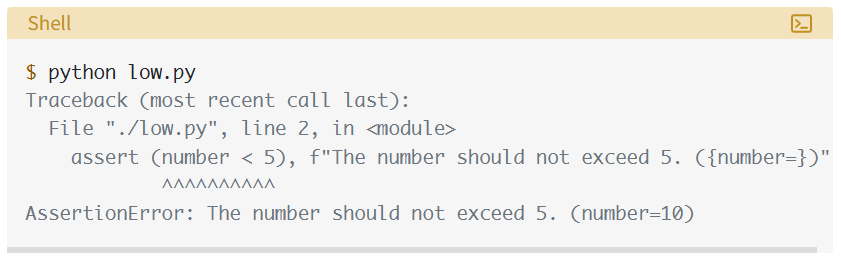

Assert – exception that’s a bit different than the others

Python offers a specific exception type that you should only use when debugging your program during development, This exception is the AssertionError. The AssertionError is special because you shouldn’t ever raise it yourself using raise.

Instead, you use the “assert” keyword to check whether a condition is met and let Python raise the AssertionError if the condition isn’t met.

The idea of an assertion is that your program should only attempt to run if certain conditions are in place. If Python checks your assertion and finds that the condition is True, then that is excellent! The program can continue. If the condition turns out to be False, then your program raises an AssertionError exception and stops right away

So you can replace the if condition with an assertion

number = 1

if number > 5:

raise Exception(f"The number should not exceed 5. ({number=})")

print(number)to this

number = 1

assert (number < 5), f"The number should not exceed 5. ({number=})"

print(number)If the number in your program is below 5, then the assertion passes and your script continues, However, if you set number to a value higher than 5—for example, 10—then the outcome of the assertion will be False and assertion will be thrown and program also stops

number = 10

assert (number < 5), f"The number should not exceed 5. ({number=})"

print(number)

Using assertions in this way can be helpful when you’re debugging your program during development because it can be quite a fast and straightforward to add assertions into your code otherwise it is not mandatory to use it in code.

In production when python code is run, it is run in optimized mode where all the assertion statements are removed, which means that assertions aren’t a reliable way to handle runtime errors in production code so it is best to raise an exception, above exercise is to only teach about assertion so when you encounter it in code in real life, you know what it is

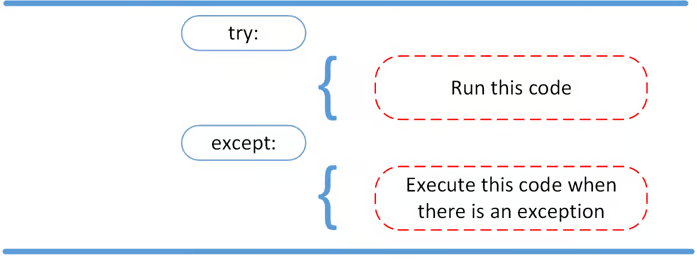

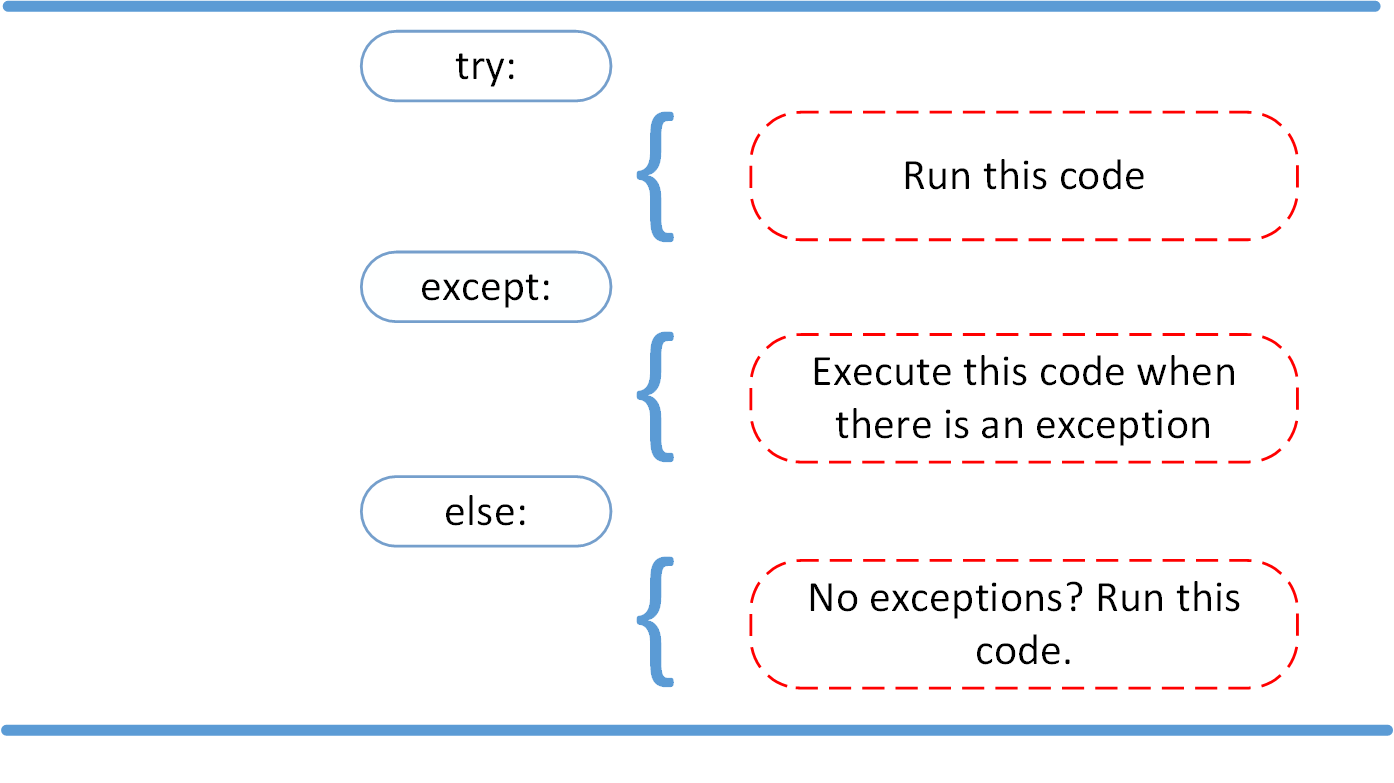

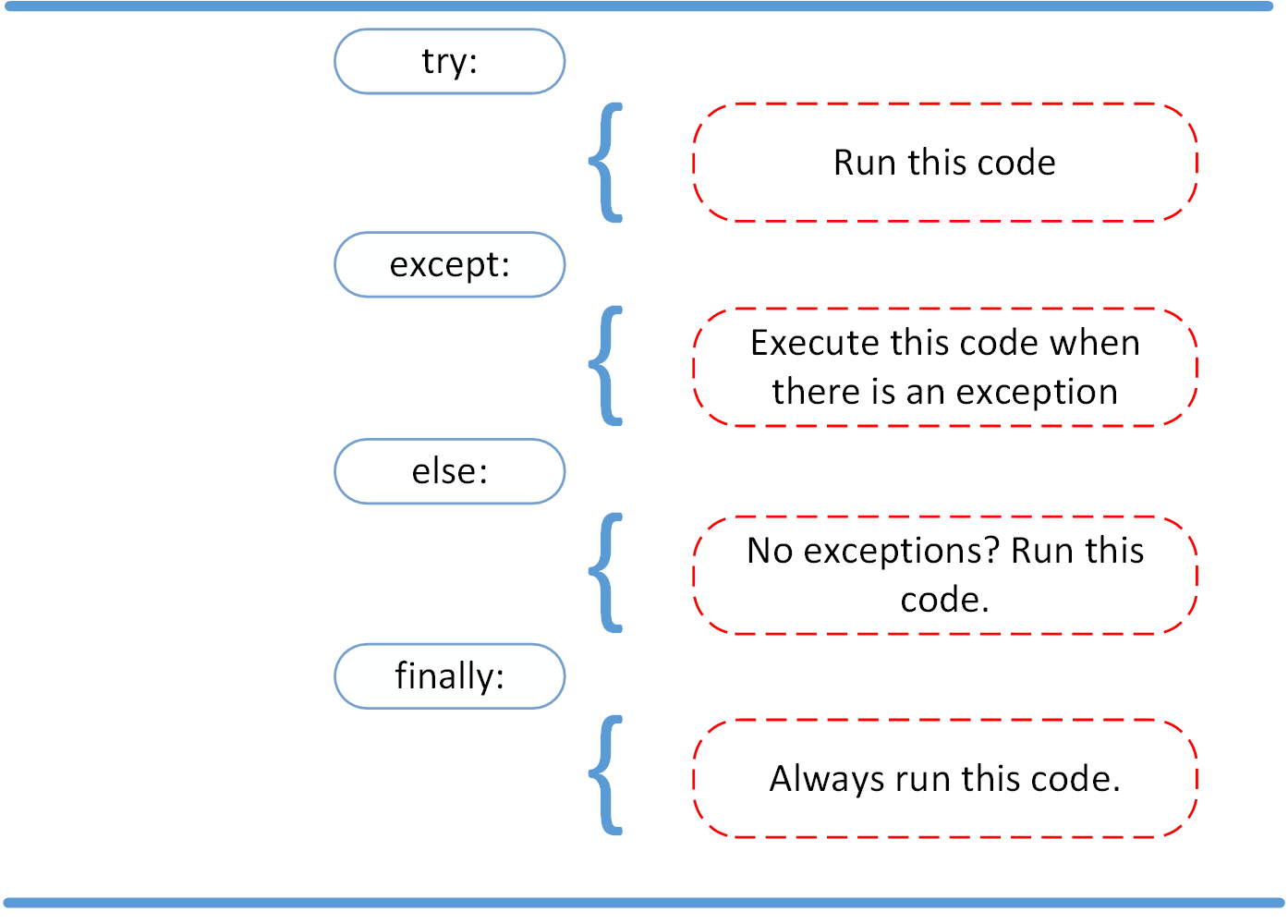

Handling Exceptions With the try and except Block

try:

some_code()

except:

passRemember except stands for exception

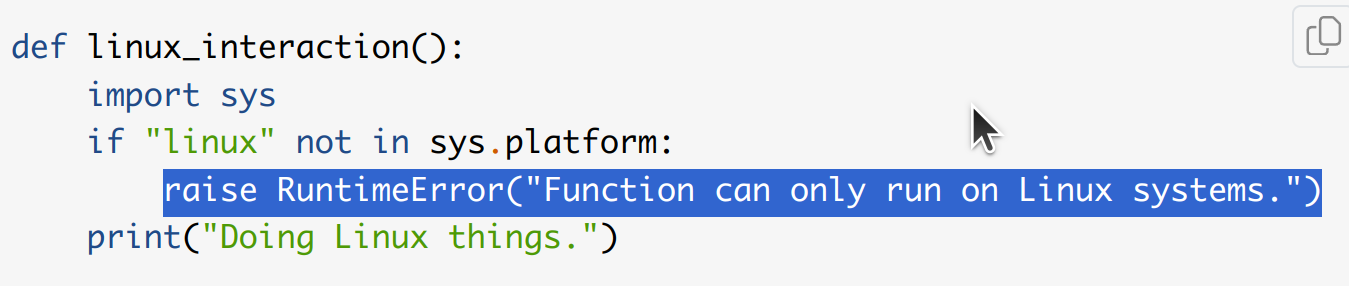

Example code for raising RuntimeError (builtin) exception.

def linux_interaction():

import sys

if "linux" not in sys.platform: